When archaeologists stumble upon ancient human remains, one of their first tasks is to identify if the skeleton belonged to a man or a woman.

But how exactly do they do it, and how trustworthy are their methods?

As Sean Tallman, a biological anthropologist at Boston University, explains, “We typically assess the shapes and sizes of bones, yet no method guarantees 100% accuracy.”

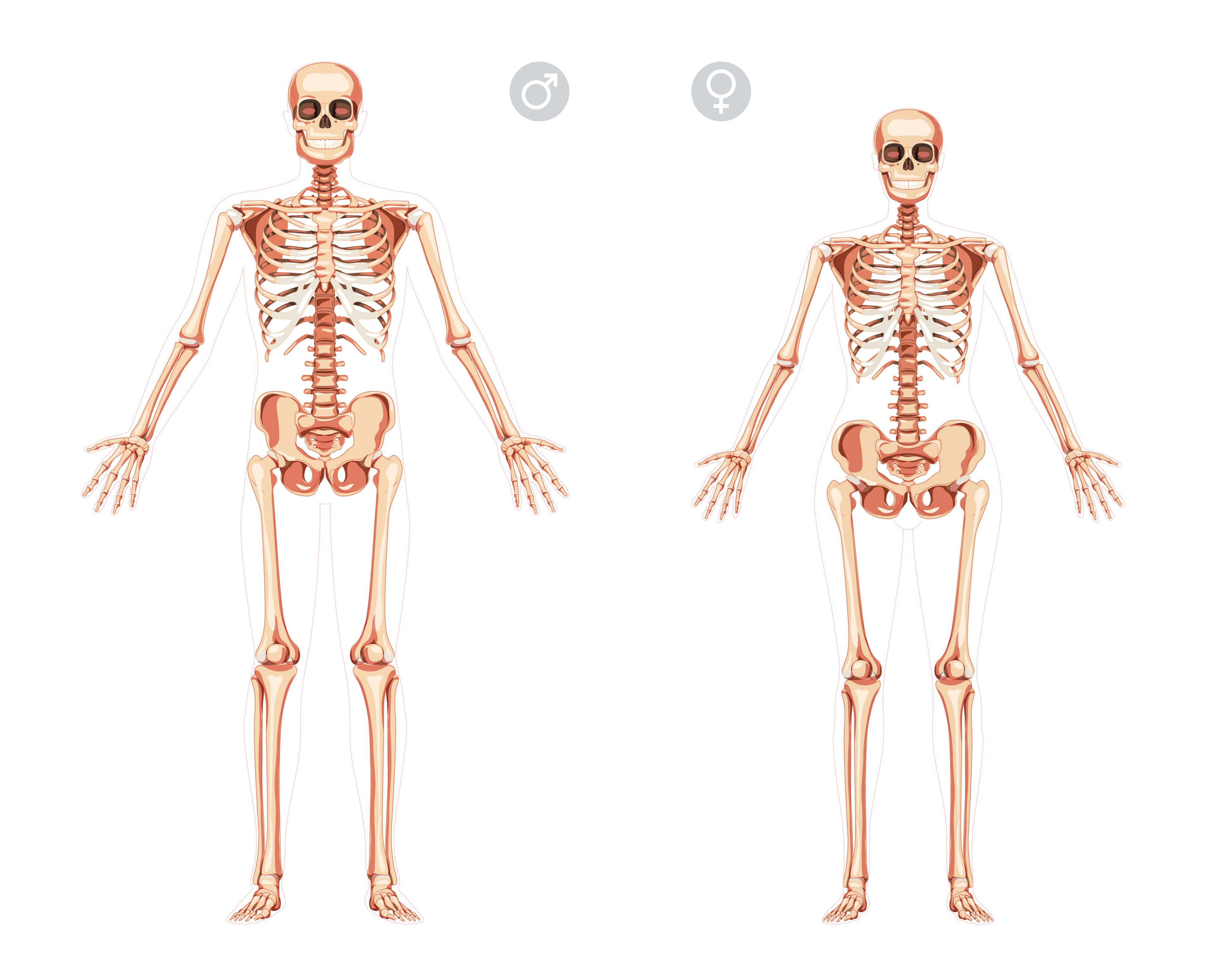

Investigators frequently measure long bones like the femur and tibia—those that make up our legs—and use statistical techniques to make informed sex predictions.

Kaleigh Best, another biological anthropologist, notes that, generally speaking, males tend to be about 15% bigger than females. However, numerous factors such as genetics, nutrition, and even environmental aspects can influence body size, adding plenty of variability even among those sharing the same sex.

Related: What is the maximum number of biological parents an organism can have?

Typically, techniques used to measure size assume that males are taller and bulkier than females, yielding sex estimates of around 80% to 90% accuracy. However, if the pelvis is well-preserved, examining its characteristics can provide clearer insight than simply measuring the upper limb bones.

The primary method for gauging sex via the pelvis is known as the Phenice method, which was introduced by an anthropologist in the 1960s. Features of the pubic bone’s shape can indicate sex: a taller pubic bone typically points to a male, while a broader one implies a female origin. Trained archaeologists can often achieve about 95% accuracy in sex estimation using this method.

Analyses of ancient DNA represents another avenue for sex estimation, particularly by pinpointing the sex-linked variant of a tooth enamel-related gene. This modern technique can now achieve approximately 99% accuracy, even with skeletons originating from archaeological digs. The caveat is that because DNA degrades over time, not all ancient bones can undergo this analysis.

Despite high accuracy, many archaeologists caution against assuming a skeleton’s sex solely based on its bones. This limitation often neglects a more complex understanding of biological sex, which includes genetics, hormones, and reproductive features. Gender, on the other hand, is shaped by culture, self-identity, and societal roles.

“Sex isn’t simply binary; it could be described as bimodal,” explains Donovan Adams, an anthropologist from the University of Central Florida. In this context, bimodal means if you plotted sex on a graph, you’d notice two peaks for male and female at either end of the spectrum, with an overlap representing intersex individuals.

Approximately 1.7% of the population is some form of intersex, according to Virginia Estabrook, a biological anthropologist at the University of Maryland, Baltimore County, indicating that about 1 in 50 people fall into this category.

Examples of intersex conditions range from congenital adrenal hyperplasia (CAH), resulting in ambiguous external genitalia, to Klinefelter syndrome marked by XXY chromosomes leading to non-standard male physical traits, in addition to androgen insensitivity syndrome and variations in sex chromosome patterns.

Estabrook analyzed the skeleton of American Revolutionary hero Casimir Pulaski, who fought bravely in 1779. His skeletal structure displayed traits typically associated with a female biological growth pattern. Nonetheless, historical documents confirmed he lived and identified as a man. One potential explanation could be CAH, which allows those categorized genetically as female to possess male-like genitalia. Furthermore, CAH individuals may exhibit secondary male traits, like facial hair growth.

This intersex case serves as a unique exploration, Estabrook remarks, “because most archaeological skeletons don’t reveal anything about the individuals behind them.”

Identifying who someone was in ancient times isn’t just tough due to the inherent limitations of biological sex assessment, but also because of the intricacies of gender.

Most identity traits—like favorite sports teams or gender roles—are socialized rather than innate. “Identity is something that needs continual performance throughout life,” says Adams. Practices typically perceived as gendered, such as archery or grain processing, can leave enduring marks on skeletons, complicating our understanding of historical cultures.

The complexity surrounding sex and gender occasionally leads archaeologists to erroneous interpretations. A case from Pompeii revealed through DNA that skeletal remains believed to belong to a mother and her biological child were, in reality, a male and a non-related child. Similarly, a remarkable Viking burial outfitted with weaponry turned out to involve a chromosomally female individual.

While DNA testing offers greater precision in sexual classification, archaeologists still grapple with the underlying issues of sex estimation from ancient remains.

“It’s genuinely challenging to detach from a binary perspective,” remarks Tallman. “There’s immense overlap between male and female physical attributes.”

Estabrook concurs, stating, “Every time we attempt to create rigid classifications within biological sex, some individuals invariably fall outside those categories.”

Another hiccup in this research is that there remains a lack of comprehensive study concerning various intersex variations affecting the estimated 1 in every 50 people who identify with these conditions.

“Future research will heavily depend on suitable federal funding,” Tallman wraps up, adding that such financial support is crucial for thoroughly interpreting behaviors and biological structures using archaeological remains.

Thanks to scientific breakthroughs, gaining insights into humane skeletal features offers unprecedented clarity, observes Best. However, navigating the identity of a person based solely on their remains is much more convoluted than previously anticipated.