Recent research has revealed that as men get older, their sperm can gather harmful DNA mutations. This accumulation might influence the mutations passed down to their children and could increase the risk of disease for the younger generation.

Mutations in DNA occur during cell replication, either due to random occurrences or through environmental influences. These mutations can either disrupt bodily functions or remain inconsequential. Over time, these genetic flaws accumulate, similar to how wear and tear builds up on a vehicle. However, until now, the extent of this impact on older men’s sperm has been unclear.

Researchers from the Wellcome Sanger Institute and King’s College London conducted an innovative analysis using a technique called NanoSeq. They examined sperm mutations from men aged between 24 and 75 years, focusing on how these mutations affect genes.

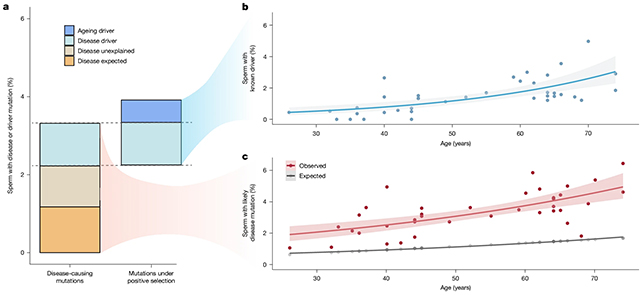

The findings indicate not only that older men experience higher mutation rates, but some mutations are described as selfish. This means that cells possessing these mutations can grow quicker, allowing them to replicate faster and dominate within the testes. Many of these mutations have previously been associated with various cancers and developmental disorders.

“We were looking for signs of mutation selection in sperm cells,” shares geneticist Matthew Neville from the Wellcome Sanger Institute. “What took us aback was the level of increase in sperm carrying mutations that can lead to serious health issues.”

The study analyzed 81 sperm samples from 57 healthy men, including some sets of twins—this helped establish a clearer distinction between age-related mutations and inherited genetic traits.

Approximately 2% of sperm from men in their 30s had mutations linked to diseases, a rate that spiked to between 3% and 5% in middle-aged and older men (43 years and above). Notably, by the time a man reaches 70, around 4.5% of his sperm may harbor potentially harmful mutations.

“Certain mutations not only persist but also thrive within the testes, which means older fathers may unwittingly risk passing these harmful mutations to their offspring,” adds geneticist Matt Hurles from the Wellcome Sanger Institute.

However, it’s important to note that not every mutation will be transmitted to future generations. Some might actually interfere with reproduction, such as during embryo development.

Further research is necessary to understand how this steady rise in DNA mutations among older men affects their children’s health. Yet, the current study sheds light on the mechanisms at play.

These findings operate as a lens for scientists, allowing for a deeper investigation into the male germline—the collection of cells tasked with passing genetic material onto the next generation, often with mixed consequences.

“The male germline is a constantly changing environment where natural selection can inadvertently favor harmful mutations, impacting future generations,” concludes geneticist Raheleh Rahbari from the Wellcome Sanger Institute.

The results of this research have been published in the journal Nature.