Imagine this: a camera built for studying the dusty dunes of Mars actually snapping photos of a cosmic bullet rocketing by at an insane speed of 130,000 miles per hour. Sounds wild, right? But that’s exactly what NASA’s High Resolution Imaging Science Experiment, or HiRISE, on the Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter did. It caught a glimpse of the interstellar comet 3I/Atlas, and here’s the kicker—it did this from just 19 million miles away, the closest anyone has come to this comet!

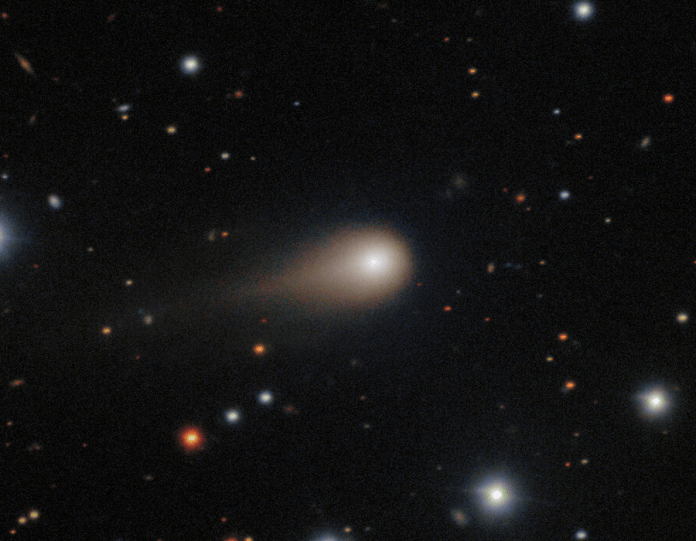

Now here’s the thing: HiRISE was never intended to capture fast-moving comets. It was designed to map Mars in stunning detail, focusing on things like rocks and dust storms with a jaw-dropping resolution of nine inches per pixel. Getting a good shot of a fleeting comet involved a ton of tricky engineering—from dealing with Mars’ thin atmosphere that can distort images, to blocking out glaring sunlight reflecting off the surface and avoiding those annoying bright stars that might wash out the comet’s dim glow. In the end, the resolution was about 19 miles per pixel, but it still provided awesome data regarding the comet’s head and its possible jet formations.

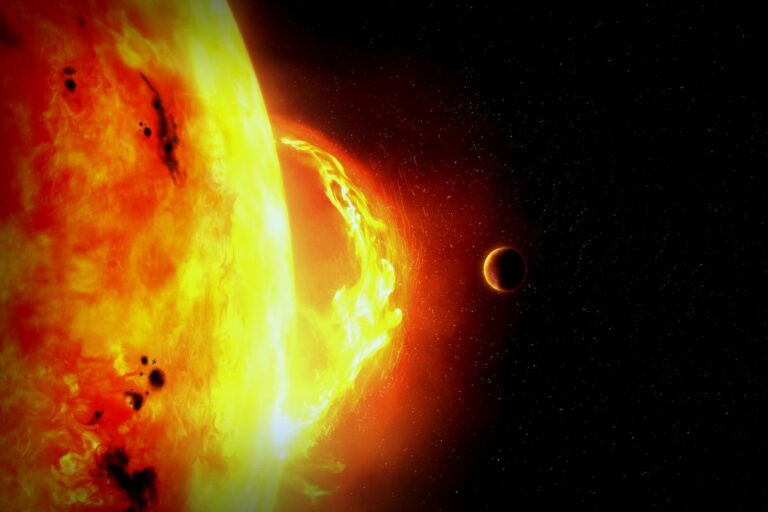

So what’s the scoop on 3I/Atlas? This comet is actually the third confirmed interstellar visitor our solar system has welcomed, following the quirky 1I/’Oumuamua back in 2017 and 2I/Borisov in 2019. With a wild trajectory and wicked speed—starting at 137,000 mph and ramping up to 153,000 mph as it neared the Sun—it’s clear this comet isn’t here to stick around. Observations made by the Hubble Space Telescope show its icy core is somewhere between 1,400 feet and 3.5 miles wide. Plus, its glowing coma, a fuzzy aura of dust and gas shaken loose by the Sun, can stretch for thousands of kilometers—with jets that could be shooting sunshine-ward as the comet heats up!

The HiRISE images might help scientists measure how the comet spins before and after it gets closest to the Sun. This info could shed light on how solar heat impacts the spinning of these strange interstellar bodies. And this data is pure gold because 3I/Atlas is behaving differently compared to usual comets we see in our solar system. Its surface chemistry, jet structure, and spectral patterns are distinct; some ground spectroscopy reveals a reddish spectrum that contains more carbon dioxide and cyanogen than the oh-so-common water vapor. Keeping an eye on such a speedy target shows just how versatile HiRISE truly is, allowing it to switch from surveying Mars to capturing distant cosmic travelers—something it did back in 2014 with Comet Siding Spring, too.

Timing played a crucial role when it came to 3I/Atlas. Earth-based telescopes couldn’t see the comet during its flyby near Mars because of Sun glare, which made the MRO the only spacecraft with a clear line of sight for a close-up snap. Not stopping there, other Mars missions joined in on the fun! The MAVEN’s ultraviolet spectrograph monitored hydrogen and hydroxyl levels in the comet’s coma, providing valuable insights about the comet’s water content and the hydrogen-to-deuterium ratio, which can help indicate where it came from. Even the Perseverance rover’s Mastcam-Z took a prolonged exposure to capture the faint trace of the comet—a testament to just how dim it was, even close by!

Sightings like this are rare gems. We know from current detection capabilities that many interstellar visitors go unnoticed as they pass through. Fortunately, the new Vera C. Rubin Observatory aims to change that by using its powerful 3.2-gigapixel LSST camera to scan the southerly skies every few nights. In the coming decade, it’s expected to identify dozens of faint and speedy interstellar bodies, although predictions on their frequency range widely—from less than two sightings a year to as much as seventy, depending on how big they are and how reflective their surfaces are.

For now, 3I/Atlas presents a unique chance to peek at matter that came together around another star, possibly eons ago. As Shane Byrne, the man in charge of HiRISE, put it, “Each time we observe interstellar objects, we uncover something new.” With the capture of this cosmic wanderer, HiRISE not only strengthens its prowess but also proves that a camera meant for one planet can, with a splash of creativity, open a broader cosmic window!