Did you know that there are more than 200 different diseases that fall under the category of zoonoses? These are illnesses that can jump from animals to humans, like avian influenza and Zika virus.

Understandably, zoonoses are often at the forefront of major health crises we encounter today. From malaria to Lyme disease and, of course, Covid-19, they play a significant role in public health discussions. In fact, it’s estimated that 60% of all infectious diseases are zoonotic, and around 75% of newer diseases that affect people work their way into our lives via animals .

For a long time, researchers have had a hunch that these zoonotic diseases started to become problematic when humans began to domesticate animals. But recent findings provide a clearer picture backed by genetic evidence.

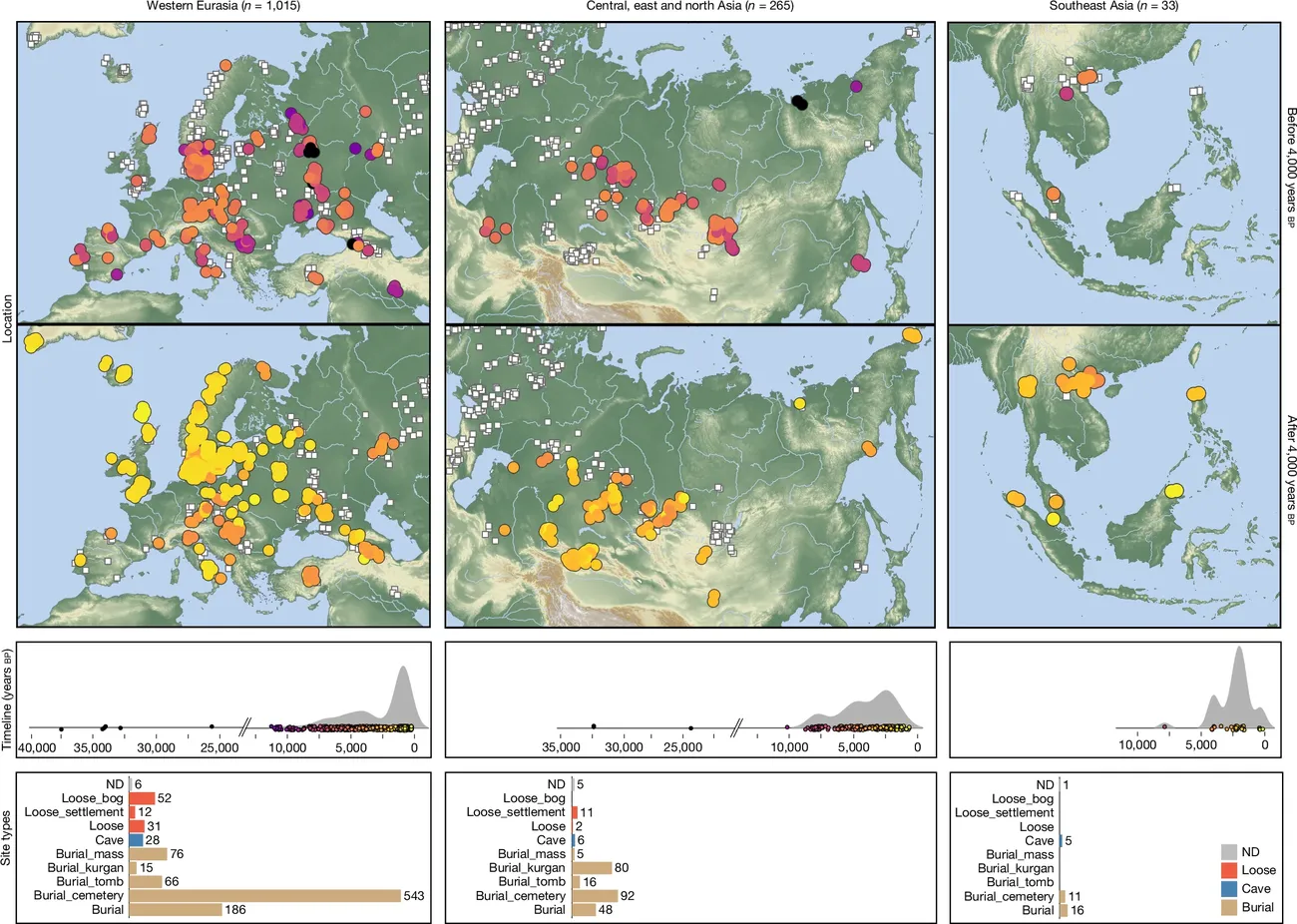

A groundbreaking study published in the journal Nature highlights that a group of scientists managed to trace the genetic lineage of 214 diseases across Europe and Asia over an incredible period of 37,000 years. Their research supports the idea that the domestication of animals fundamentally changed how humans interacted with diseases, although the timeline was a bit surprising.

According to their findings, zoonotic pathogens began cropping up about 6,500 years ago, peaking around 5,000 years ago. This timeline caught the researchers off guard, as reported by The New York Times’s Carl Zimmer. This timeline unfolded long after humans in regions like Mesopotamia were already in the process of domesticating animals . The DNA evidence suggests that these diseases likely became problematic first in regions of Asia and Russia when communities transitioned from being hunter-gatherers to settling in or farming.

Once these pastoralist groups managed to tame horses, they hit the road in oxen-pulled wagons, allowing them to travel further distances and trade not just goods, but also ideas and, unfortunately, diseases, as outlined by the study.

Virologist Edward Holmes from the University of Sydney remarked on the scale of this project: “This is a technical tour de force.” It became possible to piece together this disease history through an extensive analysis of ancient DNA from human remains. Researchers examined microbial material from 1,313 ancient skeletons and were able to pinpoint 5,486 distinct DNA sequences related to bacteria, parasites, and viruses.

While researchers are less certain about why zoonotic diseases spiked at this time, the study adds to existing considerations that this period marked a significant adaptation in immune responses, helping certain groups survive while others fell victim to what would have been new pathogens.

In fact, previous research suggests that while these nomadic peoples’ immune systems adapted, they possibly became more susceptible to chronic conditions, such as multiple sclerosis.

Grasping how diseases impacted humans thousands of years back could provide crucial insights for improving modern medicine, including vaccinations.

As Eske Willerslev, a prominent evolutionary geneticist, shared, learning from these long-past mutations can guide future vaccines to ensure widespread health safety against emerging pathogens.

Among the remarkable samples in their study is one featuring the world’s oldest trace of Yersinia pestis, the bacteria behind the Black Death that wiped out 30 to 50 percent of Europe’s population during the Middle Ages. It moves from fleas to rodents, and eventually to us, illustrating how powerful zoonoses have historically influenced humanity.

Willerslev poignantly notes that these outbreaks not only induced illness but also spurred population migrations and crucial genetic changes.

Other diseases identified within the bones analyzed included malaria (4,200 years), leprosy (1,400 years), or Hepatitis B (9,800 years), to name a few.

Nevertheless, while the insights from this massive research endeavor are compelling, the researchers emphasize its current limitations. For instance, humans host many RNA-encoded viral genes which were not explored in this research. Also, certain pathogens may have slipped through unnoticed due to low detection rates within the samples. And the historical scopes mainly relate to Eurasian sites as ancient DNA from Africa was sparsely available.

“Understanding history helps us shield ourselves against future threats,” Sikora notes in closing. “Most newly emerging infectious diseases are anticipated to have animal origins.”