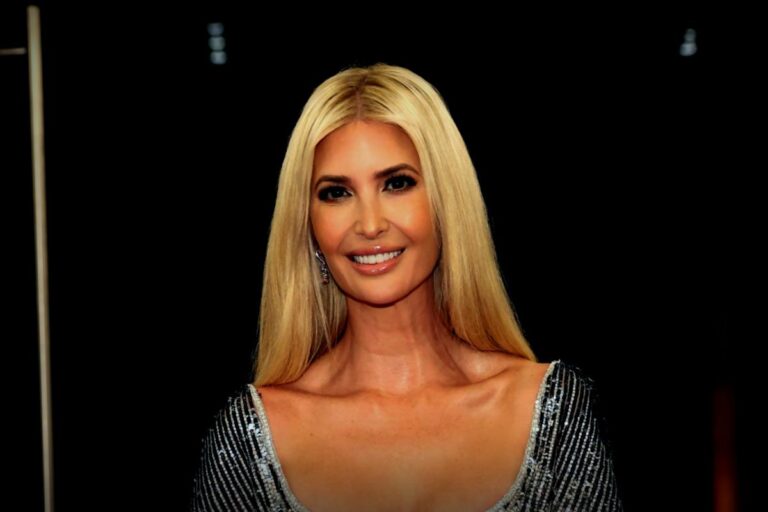

The Federal Reserve has made another cut to interest rates at its latest meeting, but Chair Jerome Powell has cast doubt on the possibility of more cuts this year.

During a press conference following Wednesday’s meeting, Powell noted that market expectations for another rate cut in December may be overly optimistic. “That’s far from a given,” he commented to the media.

This recent quarter-point cut lowers the Fed’s benchmark interest rate to a new range of 3.75% to 4%, the lowest in three years and down from the previous high of approximately 5.4% maintained for much of 2022. The reduction aims to combat a slowdown in hiring and prevent the situation from worsening.

Powell stressed that unwinding the aggressive rate hikes could be challenging, as more officials express concerns about the necessity of further cuts.

The challenge is compounded by a data blackout due to the ongoing government shutdown, which adds to uncertainty surrounding the economic outlook. This lack of data can potentially lead to more cautious decisions regarding additional rate cuts.

The Fed’s decision for the rate cut passed with a 10-2 vote. Notably, Kansas City Fed President Jeffrey Schmid opposed the cut, preferring that rates remain unchanged, while Fed governor Stephen Miran advocated for a larger cut of half a point.

In a related move, the Fed officials are set to halt their three-and-a-half-year plan to reduce the $6.6 trillion asset portfolio starting December 1. This initiative was meant to passively unwind pandemic-related stimulus efforts.

The approach adopted by officials was to stop the runoff of their Treasury holdings when banks showed signs of being less inundated with surplus cash. Recent signs have suggested this might be the case. While the Fed will continue to reduce its mortgage-backed securities holdings, it plans to reinvest maturing bonds into short-term Treasury bills starting in December.

With the anticipation of cuts already baked into market expectations, attention has shifted toward the Fed’s final gathering of the year in December. Powell noted it has generated diverse opinions on how to move forward.

Back in September, a slim majority of officials projected two more cuts this year, giving grounds to think a December cut might be probable – although a notable minority of officials argued against further reductions.

This minority is increasingly worried about rising inflation that has been sitting above the Fed’s target of 2% for several years, worsened by higher prices from tariffs implemented by President Trump.

Typically, economic data updates help resolve differing viewpoints within the Fed between meetings. However, the alignments have been disrupted lately due to missing labor market indicators, limiting insight into the changing landscape.

Without timely updates, officials haven’t acquired much new knowledge since September, leaving them facing a broader range of uncertainty, according to William English, a former senior adviser at the Fed.

Powell acknowledged the complexity of avoiding mistakes while navigating future rate cuts, expressing the concern that excessive cuts might unintentionally recipe economic engagement that could keep inflationary pressures alive. While stock markets have surged recently, there’s apprehension among officials about the potential risk of pressing too hard on the gas.

On the flip side, there is a keen awareness of the effects that past increases and changes in trade policies have had on rate-sensitive sectors, including housing, as well as on spending by both low-income consumers and smaller businesses.

In recent weeks, significant layoffs have been announced by several major employers, reflecting a more significant trend of job reductions amid the increasing adoption of artificial intelligence technologies and a realization that staffing levels may have been excessive during the rebound following the pandemic shutdown.

The shutdown further complicates Fed Chairman’s ability to track the economy effectively. Professor English highlighted that policymakers can feel uneasy when they smell something amiss but can’t pinpoint it.

The Fed cut rates by one percentage point across its last three meetings throughout 2024, but decided to halt further action as inflation displayed signs of potentially persisting above expectations. Throughout much of this year, discussions revolved around what conditions would justify rate cuts again, considering that many officials felt the rates were already healthy enough to curb economic growth.

However, evolving job market trends this summer, showing a marked decline in job growth despite slightly uptick in inflation numbers contributed to a shift in discussions about potential rate adjustments. Inflation levels have crept close to 3% after previously dipping below earlier in the year.

With insufficient indicators of action in the labor market, gaining support for larger-than-quarter-point rate cuts is complicated. Each quarter-point adjustment only raises the pertinent question about when the rate cutting should come to an end.

Recent remarks from Powell and other Fed officials in anticipation of Wednesday’s call imply that decreaseable data must outweigh all odds of new decreases ahead, creating a tougher bar to reach. With the current data blocks, Powell reasoned that December might almost require another cut. Maintaining this downward trend may become simpler than deciding to halt it.

Although inflation has taken center stage this year, the overarching discussion remains rooted in the labor market. Many officials assert that price surges tied to tariffs are less likely to recur due to potential fragility within the labor sector. The underlying belief is that a lukewarm labor approach will likely keep inflation at bay.

Policymakers are inspecting potential reasons behind the reduction in monthly job additions — whether fewer individuals are entering the labor pool or diminishing demand for positions.

The economy saw an average addition of approximately 29,000 jobs per month through August, considerably lower than 82,000 during the same period a year ago, as reported by the Labor Department.

Rate cuts can help stimulate demand but cannot mitigate scenarios where there aren’t enough people seeking jobs.

Changes in immigration policy likely contribute to a decrease in the number of new positions necessary to maintain a steady unemployment rate, suggesting a drop below 50,000 jobs per month, a notable decline from around 90,000 before the pandemic and 150,000 during immigration increases post-pandemic, as supported by various models.

James Bullard, former president of the St. Louis Fed, indicated uncertainty in adjustments of thoughts on the new threshold of 50,000 job filings being deemed satisfactory, suggesting some officials might remain unconvinced.

Robust consumer spending, driven by soaring stock markets, alongside general economic growth, could advocate against a rapid moderation in rate reductions, particularly in light of recent inflation trends. Bullard noted that a rate cut in December may present challenges amid shifting nonfarm payroll developments.

For further clarifications, feel free to reach out to Nick Timiraos at Nick.Timiraos@wsj.com