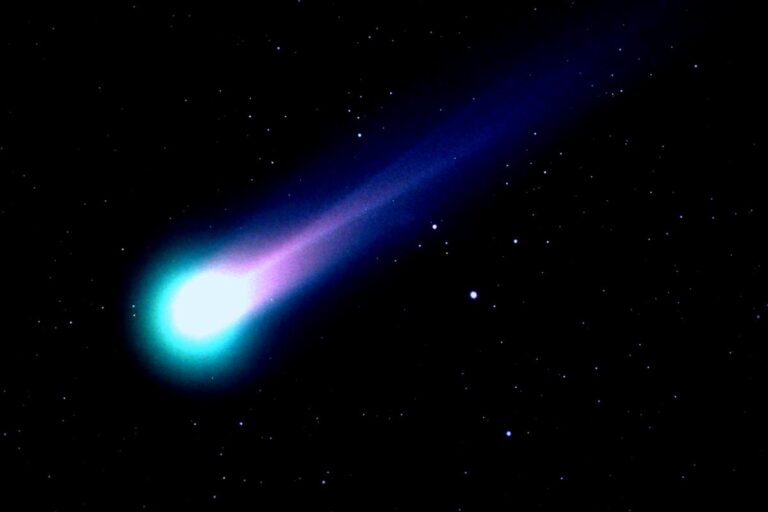

In the notorious year of 1975, the Soviet spacecraft took a bold plunge into Venus’s heavy, noxious atmosphere. After navigating through the harsh environment, it landed on a landscape that had never been witnessed by human eyes. Tragically, it could only endure for 53 minutes before the scorching heat and immense pressure took their toll. Nevertheless, within its short lifespan, Venera 9 managed to send back the very first images snapped from the surface of another planet — an extraordinary feat achieved in one of the most unforgiving locations in our solar system.

Exploring Venus is an almost insurmountable task. The planet’s atmosphere is predominantly carbon dioxide mixed with sulfuric acid, rendering it 93 times denser than that of Earth. The surface pressure is around 92 bar, comparable to being nearly a kilometer underwater, and temperatures soar to around 460°C — hot enough to turn lead into a liquid. According to Jim Garvin, the Chief Scientist at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center, “Venus is an engineering conundrum.” While there are countless scientific questions to investigate, the engineering challenges are monumental. Any lander must descend through 35 kilometers of thick, opaque atmosphere, only clearing shortly before touchdown, and needs to operate for merely a couple of hours before systems fail due to the relentless conditions.

The Soviet Union initiated the Venera program in 1961, significantly stepping up the efforts to face these extreme challenges. The initial missions, Venera 1 through Venera 6, didn’t manage to collect surface data but yielded valuable atmospheric information. Then in 1970, Venera 7 became the first spacecraft to land gently on a foreign planet, transmitting data for just 23 minutes. By 1972, Venera 8 was able to study the chemical makeup of surface rocks, hinting at geology similar to granite. But the revolutionary design was yet to come: the thickly shielded 4V-1 series landers, expertly crafted to withstand the harsh conditions on Venus long enough to send photos back home.

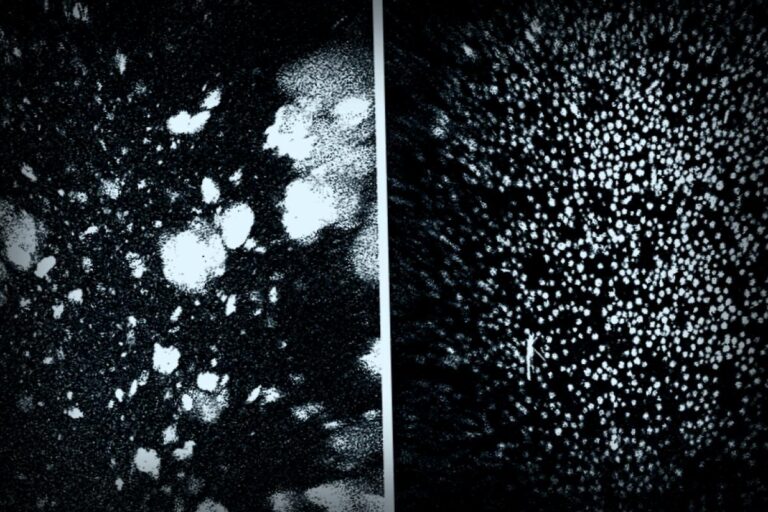

With Venera 9 and 10, the engineers devised a novel imaging technique. Direct exposure of the camera to the environment was out of the question, so a telephotometer was cleverly nestled within a pressure vessel. Light entered through a quartz porthole, redirecting through a periscope to the sensor. This innovative approach allowed the landers to scan the landscape one line at a time, creating impressive 180-degree panoramas despite the planet’s harsh surroundings. The design accommodated severe optical distortions due to atmospheric refraction and haze, yet the resulting images revealed exquisitely clear views of rocky, lava-like plains.

From a technological standpoint, these panoramas were nothing short of impressive for their time. The telephotometers methodically scanned each column, transmitting data to an orbiting spacecraft in the process. With heavy titanium walls and specialized insulation, the interior temperature remained around 30°C, while outside, it sizzled beyond 450°C. The electronics were constructed with heat-resistant materials, and all systems were designed to tackle the fiercely crushing pressure. Still, there was always that looming countdown to failure as the inevitable heat would breach the vessel’s defenses.

The data showcases Venera 9’s commendable 53-minute survival along with Venera 10’s slightly longer experience at 65 minutes, both regarded as major accomplishments. Subsequent missions, such as Venera 13, which operated for a remarkable 127 minutes in 1982 and snapped full-color panoramas of basaltic landscapes, set even new records. Improved 4V-1M landers sported dual telephotometers equipped with colored filters, revealing intricate maneuverings at the processing path under the lander. These triumphs were facilitated through remarkable technology, like the Soviet RT-70 deep-space antenna used to enhance data connection speed from 256 bits to a whopping 3,000 bits per second, producing stunning imagery before their unavoidable shutdown.

The photographs — showcasing yellow-orange skies, fragmented rocky plates, and the fine dust stirred up during descent — pay homage, not far from the realms of materials science, to the struggles of planetary exploration. The endurance needed for even a fleeting survival period on Venus required specially designed alloys and seals capable of withstanding supercritical carbon dioxide, extreme temperature variations, and mechanical stresses akin to underwater trenches. The Soviet approach involved crafting the lander as a pressure vessel, reminiscent of undersea explorers, but with the added challenge of raging heat.

Merely four spacecraft — Venera 9, 10, 13, and 14 — have s ded in capturing and transmitting images from Venus’s surface. This extensively represents our rare first-hand visual records of a planet that may have once shared conditions with Earth before its dramatic shift in climate. Just as Ted Stryk, who has painstakingly reconstructed the original panoramas from raw Soviet information, remarked; these images are fleeting looks into an environment so menacing that even our most advanced robotic explorers struggle to endure its fury.