On December 26, 1898, a group of chemists made a stunning discovery: a substance that was 900 times more radioactive than uranium! Their findings would pave the way for groundbreaking advancements in medicine and launch them into the limelight, but it would come with a hefty price — the life of one of them.

Marie Curie was studying at the prestigious Sorbonne in Paris when she became captivated by the emerging field of radiation, which would serve as the basis for her thesis. This newfound interest was sparked in part by the discovery of “Röntgen rays” by Wilhelm Röntgen in 1895 and the accidental finding of weak rays from uranium salts by Henri Becquerel in 1896. These rays had a curious power — they could fog photographic plates even without light exposure! You can read more about it here.

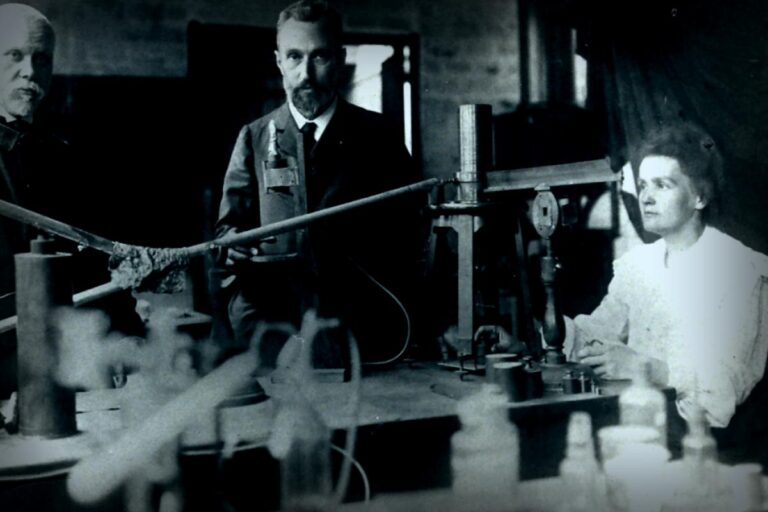

Curie’s breakthrough moment came when she realized she could skip the lengthy literature review phase and dive directly into experiments. Her husband, Pierre, found her a space in a cluttered storeroom at the Paris Municipal School of Industrial Physics and Chemistry. He soon became engrossed in her work, deciding to put his projects on hold to join her.

A vital piece of Curie’s research was the piezoelectric quartz electrometer crafted by her brother-in-law, Jacques Curie, which allowed her to measure the weak currents generated by radioactivity. Marie explained her innovative approach in a 1904 article published in Century Magazine, where she stated that instead of using photographic plates, she preferred to gauge radiation intensity through air conductivity.

The dingy storeroom was less than ideal, but Curie discovered that the intensity of radiation was linked to uranium concentration within the minerals she was examining. This spurred her intuition — there must be something intrinsic to uranium’s atomic structure that explained these findings.

Teaming up with Pierre and Gustave Bémont from the Higher School of Industrial Physics and Chemistry, the group turned its attention to pitchblende, a black mineral rich in uranium often found alongside silver deposits.

Marie noted it exhibited far higher radioactivity than uranium ore alone. “How can an ore made of inactive elements be more active than the active substances from which it was created?” she pondered, concluding that the ore must contain a new, unidentified element even more radioactive than uranium and thorium.

Despite the challenges, the trio persevered and endeavored to separate pitchblende into individual elements, employing light spectra to isolate and categorize the components. In July, they discerned one mineral exhibiting 60 times the radioactivity of uranium, which they appropriately named polonium. Then, on December 21, they announced the discovery of radium, a substance boasting an astonishing 900 times the radioactivity of uranium! Their findings were presented during a meeting at the French Academy of Sciences on December 26.

Over the next few years, the Curies isolated these radioactive elements, all while working in a poorly ventilated shed in a courtyard near their original workspace. Their tireless efforts led to a Nobel Prize in Physics awarded in 1903, shared with Becquerel. Although initially overlooked, Marie secured her rightful place in history thanks to her husband’s insistence on acknowledging her crucial contributions. Marie later won a second Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 1911 for her work with radium.

Tragically, Pierre’s life was cut short in 1906 due to an accident involving a horse-drawn carriage, but Marie continued to pioneer the application of X-rays in medicine. She famously developed mobile X-ray units for battlefield use during World War I and discovered that radium targeted diseased cells more effectively than healthy ones, providing inspiration for future cancer therapies.

However, the fallout from their research took a toll on both Marie and Pierre, with chronic radiation exposure leading to severe illness. Marie ultimately succumbed to aplastic anemia in 1934, a form of leukemia associated with prolonged radiation exposure, at the age of 66. It’s remarkable to note that her historic discovery notebook remains radioactive and is kept in a lead container!