Way back before the infamous Black Death wreaked havoc across Europe during the Middle Ages, an even older, mysterious strain of the plague was making its rounds across Eurasia.

For ages, scientists were puzzled over how this ancient plague manage to disperse so widely during the Bronze Age, which was between roughly 3300 and 1200 B.C., especially as it wasn’t transmitted by fleas like the plagues that followed. The good news is that researchers might have just stumbled upon a breakthrough clue thanks to a 4,000-year-old domesticated sheep.

In a fascinating discovery, scientists identified the plague bacteria, Yersinia pestis, lurking in a tooth of a Bronze Age sheep found in what we now call southern Russia, as detailed in a study published in the journal Cell. This is actually the very first evidence indicating that the ancient plague affected animals too, not just humans, and offers a vital piece of the puzzle regarding how the ailment spread.

NEW INSIGHTS INTO A VACCINE FOR THE PLAGUE BACTERIA

“This discovery sent alarm bells ringing for our team,” noted study co-author Taylor Hermes, an archaeologist from the University of Arkansas focusing on ancient livestock and how diseases spread. He emphasized that this was our first encounter of recovering the Yersinia pestis genome from a non-human sample.

According to the team, it was an unexpected stroke of luck to make this find.

“Whenever we analyze ancient livestock DNA, we often end up with a chaotic mix of different genetic material,” Hermes remarked, adding that while this presents a big challenge, it also opens up opportunities to find pathogens linked to herds and the people looking after them.

PATHOGEN DISCOVERY THAT FINALLY HELPED UNDERSTAND NAPOLEON’S ARMY DEBACLE 213 YEARS LATER

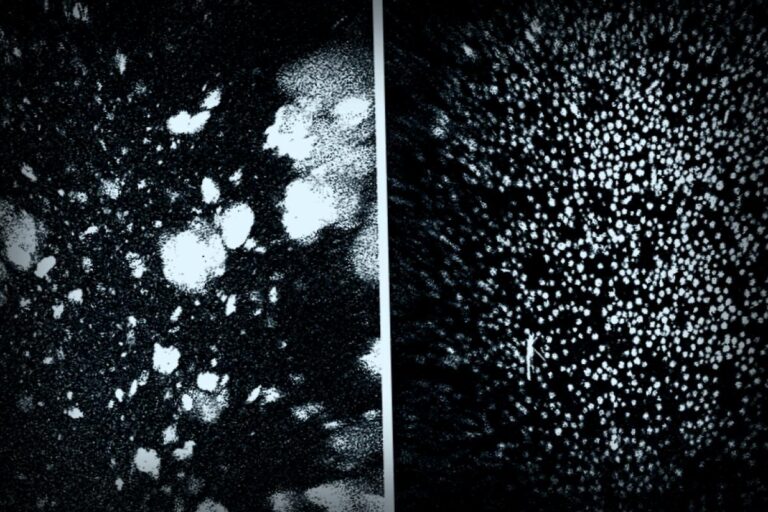

Figuring out this process is usually pretty intense and can take a lot of time. Researchers have to extract tiny, often damaged fragments of DNA from the ancient samples while sorting through contamination from soil, microbes, or even modern humans. The fragments they manage to recover can be pretty minuscule, sometimes barely holding 50 “letters” compared to the massive 3 billion “letters” in a full human DNA strand.

Researchers noted that when it comes to studying animal remains, it’s even trickier, as these remains often didn’t receive the same care as human bodies that were respectfully buried.

JOIN OUR LIFESTYLE NEWSLETTER FOR MORE

This discovery gives fresh insight into the likelihood that this plague spread through interactive living conditions between people, livestock, and wild animals, particularly as Bronze Age communities began managing larger herds and traversing wider distances with their horses. The Bronze Age was marked by heavier usage of bronze tools, comprehensive animal herding, and enhanced travel—all elements that could have facilitated disease transmission between animals and humans.

“There had to be more than just human movement involved,” Hermes said. “Our ‘plague sheep’ helped us have this breakthrough. We now recognize it as a dynamic interplay between humans, livestock, and a possibly unidentified ‘natural reservoir’ for the disease.”

DISCOVER MORE LIFESTYLE STORIES

The team surmises that sheep might have contracted the plague from other animals, like rodents or migratory birds, some of which could carry the bacteria without displaying any illness symptoms themselves, subsequently transmitting it to humans. The findings cast light on the many hazardous diseases that begin in animals before finding their way to humans—a scenario that persistently continues as we encroach upon new environments and develop closer ties to wildlife and farm animals.

“In understanding these dynamics, we must have greater respect for the powers of nature,” Hermes stated.

This research leans heavily on a sole ancient sheep genome, therefore drawing more broad conclusions remains a work in progress, and they mentioned that they need more samples to comprehensively grasp the disease’s spread.

Research efforts will proceed as they investigate more human and animal remains from the region to uncover how extensive the plague was and identify which species likely contributed to its dissemination.

Additionally, they are hopeful about pinpointing the wild animals that originally transmitted the bacteria. This could refine their understanding of how human transitions and livestock herding permitted this disease to traverse vast distances, highlighting insights that may better equip us in anticipating how animal-borne diseases will emerge in the future.

GET FOX NEWS APP TO STAY UPDATED

The study was led by researchers from the Max Planck Institute for Infection Biology, with senior authors Felix M. Key from the same institute and Christina Warinner from both Harvard University and the Max Planck Institute for Geoanthropology.

The Max Planck Society contributed support for the research, which includes plans for follow-up studies in the same area.

Original article source:Ancient plague mystery cracked after DNA found in 4,000-year-old animal remains