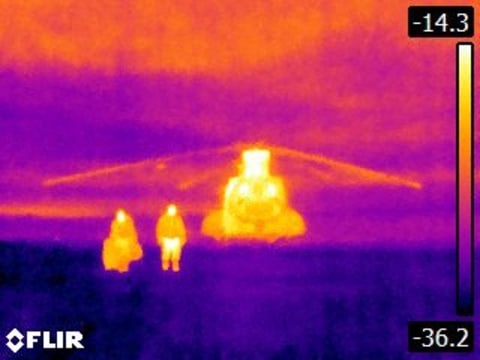

Utilizing drones and robots for combat is certainly a modern military trend, and seemingly a no-brainer in the icy wilderness of the Arctic.

However, as you venture closer to the North Pole, that high-tech gear isn’t as reliable. Magnetic disturbances wreak havoc on satellite signals, freezing temperatures can zap batteries or put equipment out of commission rapidly, and snowy landscapes make navigation particularly tricky.

Take this year’s polar drill in Canada that involved seven nations—the U.S. military’s all-terrain arctic vehicles malfunctioned after only 30 minutes due to hydraulic fluids freezing.

Even pricey military night vision goggles worth $20,000 failed Swedish troops when the aluminum construction couldn’t stand up to temperatures dipping to minus 40 degrees Fahrenheit.

According to Eric Slesinger, a venture capitalist and former CIA officer investing in defense tech startups, “The Arctic is the ultimate adversary.”

When it comes to gear in temperatures that harsh, trends seen in Ukraine don’t quite cut it. Solutions sourced from retailers often need significant tweaking to withstand Arctic realities.

Competition among world powers is intensifying in the High North, especially as melting ice opens up new shipping routes and access to natural resources. Russia holds a powerful position there, boasting nuclear submarines and missile bases along the Kola Peninsula, alongside their airfields and ports. It’s noteworthy that the quickest route for Russia’s hypersonic missiles headed towards North America crosses right over the North Pole.

Among the eight countries with Arctic territory, only Russia is outside of NATO. This leads to unique dynamics: the main concerns for the U.S. and Canada revolve around Russian missile threats, while countries like Finland and Norway, with land borders close to Russia, face potential ground incursions.

Conflict in the Arctic would see military planners revert to fundamental strategies. The severe cold can make crucial components brittle, while snags such as rubber seals becoming non-functional are not unusual, risking leaks. Any moisture can freeze into ice crystals that can disrupt machinery. Designers have to think carefully about insulation—silicone cables are preferable to PVC, which is prone to cracking under cold stress.

Certain oils and lubricants would thicken or solidify, turning most hydraulic systems sluggish, which could hamper anything from aircraft systems to missile launchers. One major freeze-up can ground an entire operation.

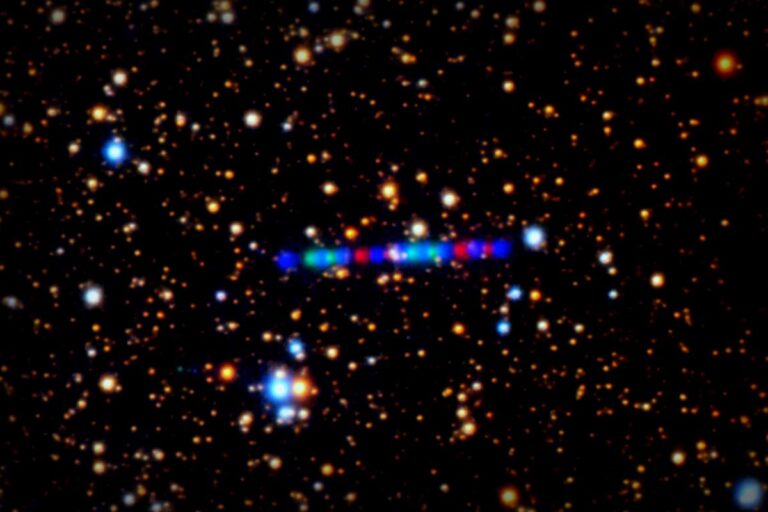

The breathtaking northern lights, a staple of Arctic tourism, can pose significant problems for strategic operations. The Aurora Borealis affects radio communication and satellite navigation, which are vital for positioning and operation coordination.

A lesson that’s clear from the conflict in Ukraine is that collaboration between private innovation teams and governments could drive pivotal advancements.

For instance, pioneering explorers Ben Saunders and Frederick Fennessy recently founded Arctic Research and Development, a startup committed to deploying autonomous systems in frozen environments. With substantial experience in the Arctic wilderness, their team has abilities in fields like space science and military tech. Investors like Slesinger are backing their mission.

They are creating specialized software for the Arctic, crafting virtual maps that truly represent the scorched, distorted areas often seen in regular world projections. Their prototyping lab in England includes a massive freezer simulating temperatures as low as minus 94 Fahrenheit for rigorous testing.

Saunders raised an interesting question: “Why do we have robots on Mars both collecting colors and sending data, yet no autonomous vehicles navigating the Arctic greens?” It’s a vast area historically unfairly illustrated on maps.

The company is working on a unique product named Icelink—a portable communication hub, lightweight and equipped with advanced GPS systems and batteries providing days of operational coverage.

Saunders understands breaks in micro-gear can have big consequences. On a solo Arctic trek, he broke a ski binding, leading to an entire trip—costing over $200,000—being cut short.

Warfare in the Arctic will come with drastically different challenges than in other locales. UAVs used in Ukraine are produced in droves and are adept in urbanized territories, where they’re capable of navigating via wireless connectivity to accomplish their missions. Unfortunately, in the Arctic, drones must cater to high-wind conditions and possess de-icing tech, running on fuel instead of batteries, often hefty enough to require trailers or runways for deployment.

Sustaining power for radios is a real challenge. Just recently, the Swedish military learned of a sled-carryable charging system weighing over 400 pounds—but it’s designed so impractically, struggles would arise solely due to snow accumulations.

According to Frederik Flink, a commanding officer in Sweden’s warfare center, many concepts from tech companies don’t reflect the genuine needs of troops on the ground. They have their practical ideas; however, these might not mesh with ground realities.

The Subarctic Warfare Center gave crucial feedback over the last few winters to a U.S. firm striving for a better cross-country ski bindings designed for durability.

Artificial intelligence isn’t always your friend in Arctic conditions. It’s gotten more valuable for quick decision-making during rapid information processing in populated eastern Ukraine. The Arctic presents quite the contrast, featuring sparse populations—often only around five per square mile—leading to limited infrastructure and resources that AI could effectively analyze.

Given the landscape, human-made disruptions have different impacts in high-latitude regions. Satellites positioned around the equator struggle with their signal due to Earth’s curvature, leading to an even worse frequency malfunction in emergencies.

In 2019, GPS failures spiked in Norway’s north near Russia, with six reported issues; by 2022, they soared to 122 as Russia’s activities next door escalated. As of late 2024, jamming issues prompted regulators to stop keeping count.

“We better adapt to these scenarios and create reliable solutions,” emphasized Espen Slette, head of spectrum management at Norway’s communications authority, Nkom.

Consequently, over a hundred firms gathered on the Norwegian island of Andøya this past September for Jammertest, a tech showcase assessing devices against interference in the ruthless Arctic atmosphere.

Heidi Andreassen from Testnor, which oversees Jammertest, attributes the jamming to Russia’s protective maneuvers for its assets in Kola, rather than outright aggression aimed at Norway.

“You really see that in rough Arctic conditions—banning communications can be keenly impactful,” said Andreassen, “It was an infrequent concern, but now numbers indicate a rising problem.”

Contact Sune Engel Rasmussen at sune.rasmussen@wsj.com