In a remarkable leap for marine research, researchers utilized drones to collect samples from the breath—often referred to as “blow”—of humpback, sperm, and fin whales found in northern Norway. This method represents a serious advancement in non-invasive health monitoring practices for these majestic ocean giants in Arctic waters.

This new method of pathogen screening has provided the first evidence that a potentially fatal virus known as cetacean morbillivirus is present above the Arctic Circle.

Experts believe this drone technology could enhance conservation efforts by identifying early warnings of viral threats that have been linked to mass strandings of whales and dolphins globally.

How Drone Sampling was Carried Out

The study, spearheaded by King’s College London and The Royal (Dick) School of Veterinary Studies in the UK, alongside Nord University, was published in BMC Veterinary Research. The researchers deployed consumer-grade drones equipped with sterile Petri dishes to hover over the blowholes of whales, effectively capturing respiratory droplets.

Professor Terry Dawson from King’s College London expressed enthusiasm about this technique, saying, “Drone blow sampling is a game-changer. It allows us to monitor pathogens in live whales without stress or harm, providing crucial insights into diseases in our rapidly changing Arctic ecosystems.” Over the period from 2016 to 2025, scientists sampled humpback, sperm, and fin whales throughout the Northeast Atlantic, inclusive of areas like northern Norway, Iceland, and Cape Verde.

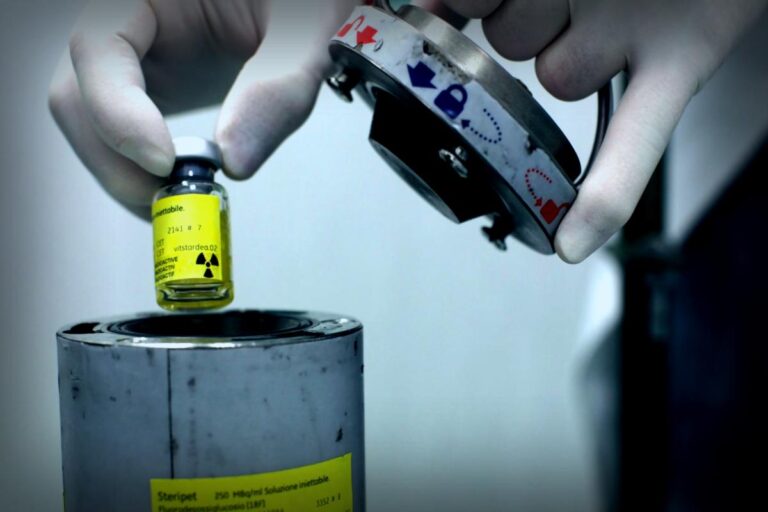

They collected blow samples, alongside skin biopsies and an organ sample in one instance, screening these for infectious agents via advanced molecular lab tests.

Key Discoveries and Health Implications for Whales

The team discovered cetacean morbillivirus, a strain initially identified in dolphins, affecting humpback whale clusters in northern Norway, a sperm whale in poor health, and a stranded pilot whale.

This virus is notably dangerous, causing severe respiratory, neurological, and immune issues in whales, dolphins, and porpoises. Furthermore, it has led to several mass mortality events in cetacean populations since its first identification in 1987. Alarmingly, these findings suggest outbreak risks during winter feeding congregations, where whales, seabirds, and humans often share close quarters.

Additionally, herpesviruses were identified in humpback whales from Norway, Iceland, and Cape Verde. However, tests did not reveal the presence of avian influenza or the bacteria Brucella, which are also connected to strandings.

This research underscores the essential need for ongoing surveillance, as pathogens like morbillivirus could significantly threaten whale populations while interacting with a host of other stressors.

According to Helena Costa, the lead author from Nord University, “Moving forward, we must keep applying these techniques for long-term monitoring, so we can understand how various emerging challenges will impact whale health in the years to come.” This study showcased collaboration with UiT The Arctic University of Norway, the University of Iceland, and BIOS-CV in Cape Verde.

For further insights, check:BMC Veterinary Research (2025)

Provided by King’s College London

This report was initially published on Phys.org.