The huge distances wolves travel in Mongolia, estimated at over 7,000 kilometers each year, and the Arctic tern’s epic pole-to-pole migrations may make humans look like lazy couch potatoes in comparison. Yet, a groundbreaking study from the Weizmann Institute of Science suggests we’re playing a much larger role in nature’s narrative than we might think.

According to new research published today in Nature Ecology & Evolution, human movement is now 40 times more extensive than that of all wild land mammals, birds, and arthropods combined. Since the Industrial Revolution—a mere 170 years ago—the frequency and scale of human travel have exploded, while animal mobility is declining, jeopardizing ecosystems.

This study brings together findings from the lab of Prof. Ron Milo, examining how humans are reshaping not just landscapes, but the intricate dance of nature and wildlife.

The researchers developed a new metric called the biomass movement index, calculated by multiplying the total mass of a species—representing all its individuals—by the overall distance that species covers in one year. This method allows for a fresh perspective on the global movement of animal species, which they then juxtaposed against human movement.

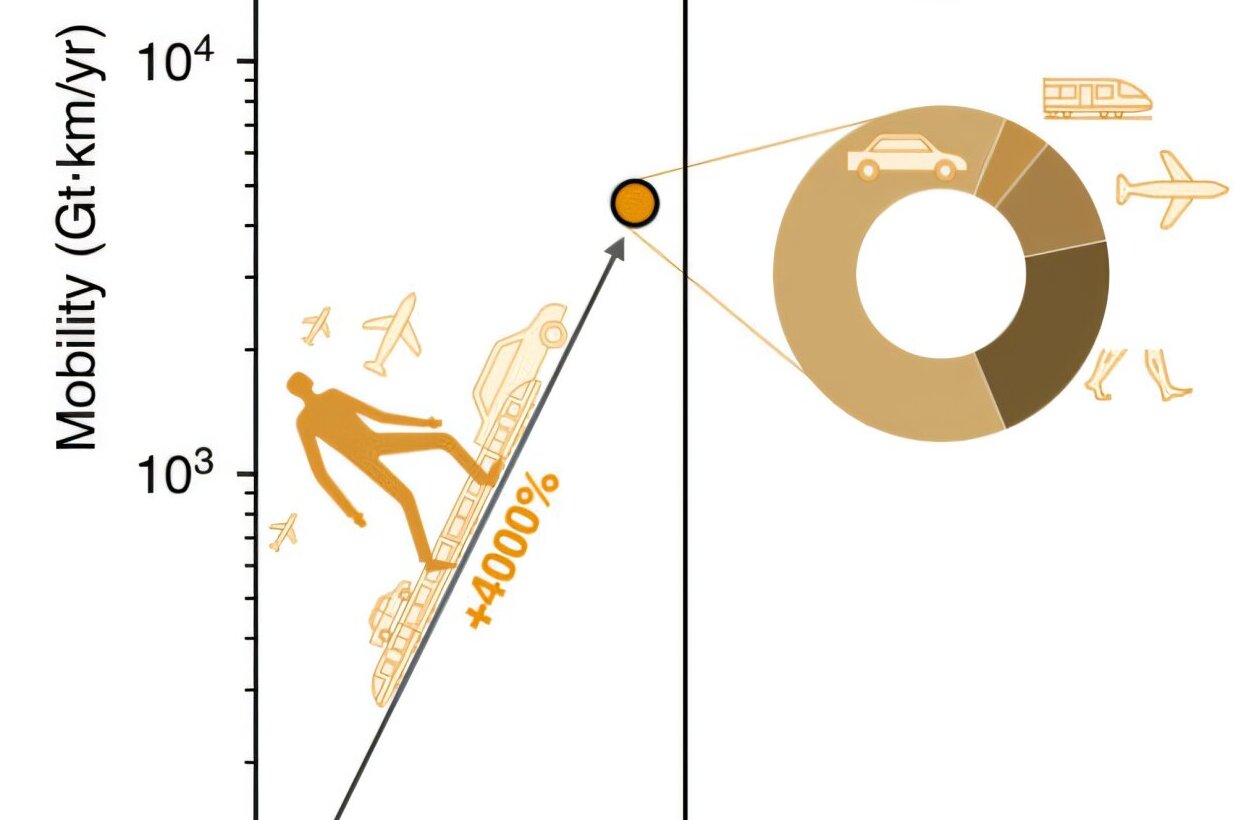

Interestingly, when it comes to how we move, about 65% of our biomass transportation happens in cars or motorbikes, 10% via airplanes, 5% by trains, and approximately 20% on foot or bicycles. What’s astonishing is that just our walking alone surpasses the movement of all wild land mammals, birds, and arthropods combined by six times!

On average, individuals travel around 30 kilometers daily through various modes of transport—a figure that slightly eclipses the distance covered by wild birds. In stark contrast, wild land mammals, if we exclude bats, only cover about 4 kilometers daily. Even in the skies, our airplane travel accounts for ten times more biomass movement than all flying animals together.

Prof. Milo emphasizes, “While we often think about the power of nature, it’s kind of shocking to realize that even the significant migrations in nature documentaries, like those in Africa, fall short of the biomass movement we see when people gather, such as during the World Cup.”

The study explains how the energy spent on movement varies across species. For instance, one airplane uses as much energy as all wild birds together. The implication? Our impact on nature may be even grander than we’d imagine.

This shifting balance is concerning; just as humanity expands and paves over more of Earth, wildlife faces steep declines. Much of the movement is still occurring within the oceans, but here too, humans are creating serious disturbances.

Dr. Yuval Rosenberg, who spearheaded the study, notes, “Ever since the Industrial Revolution, our movement has rocketed by 4,000%, while marine animals have seen a drastic drop of around 60%. Understanding that animal movement is essential for ecosystem functionality is incredible, and the global drop is indeed alarming for us all.”

Alongside Dr. Rosenberg, the study also included contributions from Dr. Dominik Wiedenhofer, Dr. Doris Virág from BOKU University in Vienna, and several researchers from the Weizmann Institute and other prestigious institutions.

A 170-Year Perspective

Typically, animal populations don’t vanish instantly; they decline over time. Often, they reach a tipping point where their diminished numbers canít fulfill their ecological responsibilities, leading to significant consequences in nature.

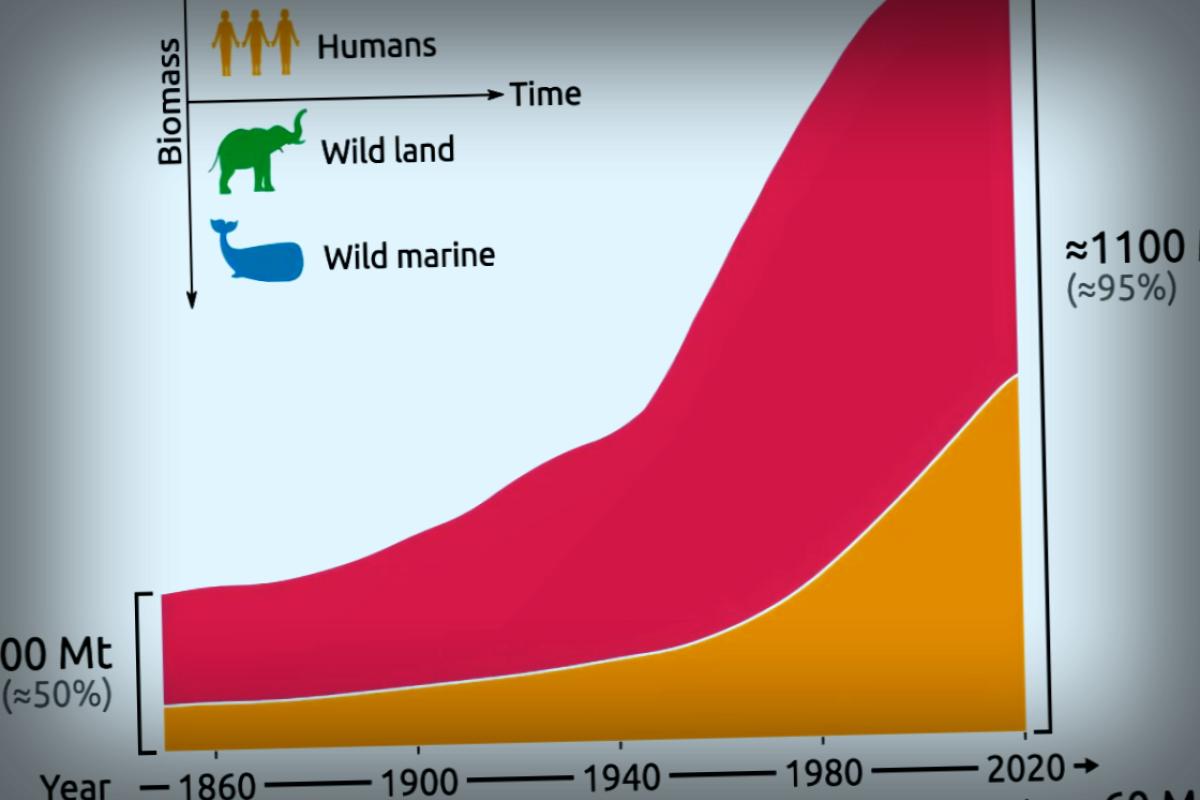

An additional paper, also published today in Nature Communications, sees Milo’s team calculating the overall biomass of all mammals on the planet since 1850. They shockingly found that wild land and marine mammals have faced a combined decline of approximately 70%, from 200 million tons back in the day to a mere 60 million tons today.

Contrastingly, human biomass has skyrocketed by about 700%, and that of domesticated animals has increased by 400%, now adding up to roughly 1.1 billion tons. This stark growth demonstrates humanity’s overwhelming dominance over wildlife and hints at the magnitude of our ecological impact. According to Milo, “The decline of marine mammals, which now sit at only 30% of their 1850 biomass, is particularly worrisome. Heavy industrial hunting has severely impacted these populations, especially in the mid-20th century.”

Some species may recover if we act swiftly, but it’s infinitely more effective to prevent hunting of vulnerable populations in the first place.

Further read: Yuval Rosenberg et al., “Human biomass movement exceeds the biomass movement of all land animals combined,” Nature Ecology & Evolution (2025). DOI: 10.1038/s41559-025-02863-9

Lior Greenspoon et al., “The global biomass of mammals since 1850,” Nature Communications (2025). DOI: 10.1038/s41467-025-63888-z

Provided by Weizmann Institute of Science