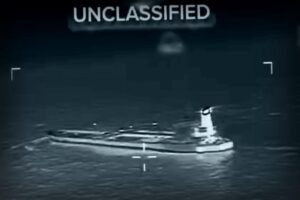

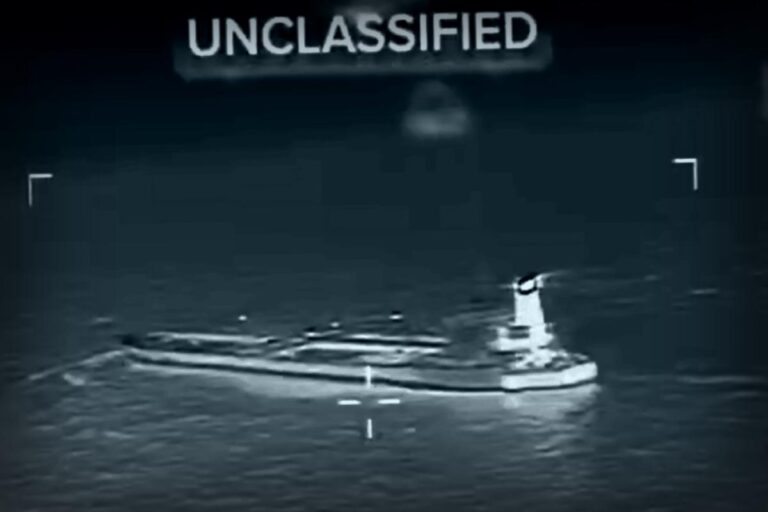

Back in 2011, researchers made a remarkable find off the beach of Los Angeles—corroded metal barrels sitting silently at the ocean floor. Some of these barrels were intriguingly wrapped in ghostly white halos within nearby sediment. Initially, the fear was that these barrels contained DDT, a toxic pesticide banned years ago, owing to the heavy pollution around them. But now, it seems there’s more to the story.

The latest findings suggest that not all these barrels might house DDT. Instead, research published on September 9 in PNAS Nexus hints that at least some barrels could hold caustic alkaline waste instead.

Getting to the bottom of where these barrels came from isn’t clear-cut. Many years ago, spanning the 1930s to the early 1970s, agencies like the Environmental Protection Agency approved various sites for dumping waste under the sea. In this timeframe, layers of landfill-like materials included everything from chemical and military waste to oil residues.

David Valentine, a microbial geochemist from UC Santa Barbara, stumbled upon the first set of these barrels over ten years ago. However, it wasn’t until 2020 when Los Angeles Times journalist Rosanna Xia drew substantial media attention to the dumping area’s forgotten history with an in-depth report.

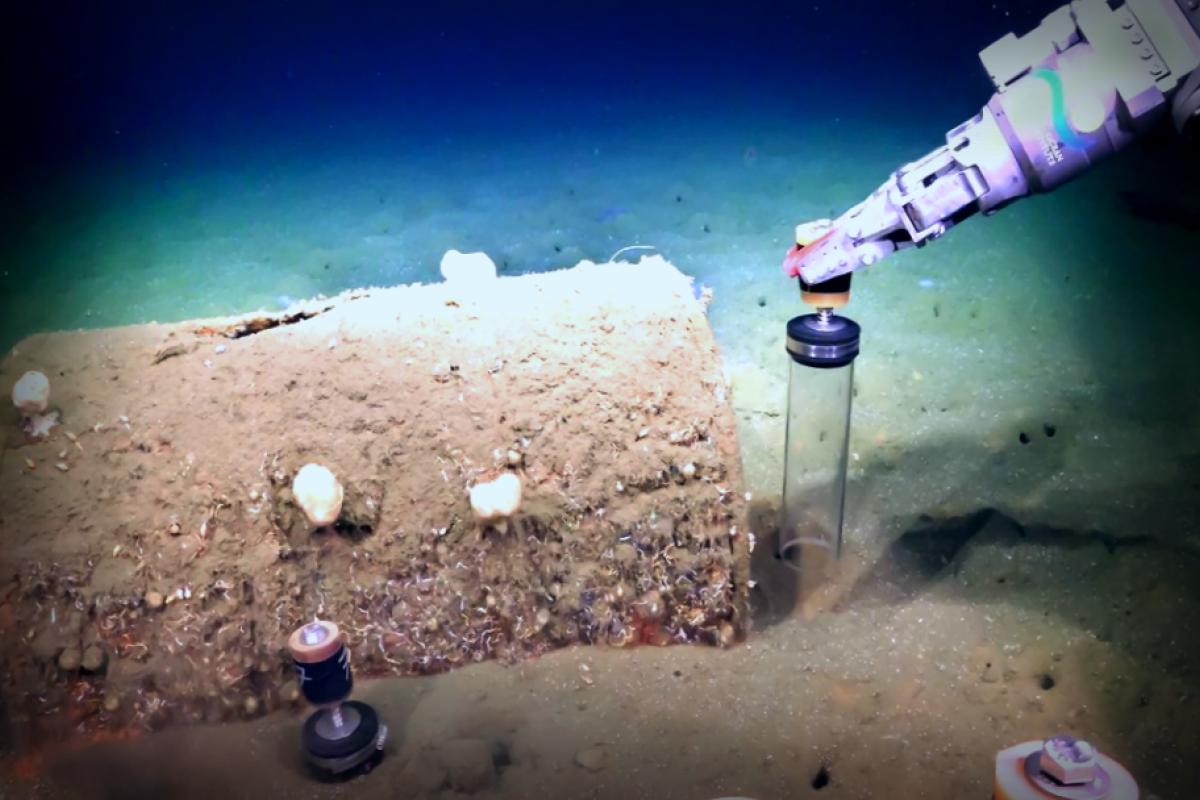

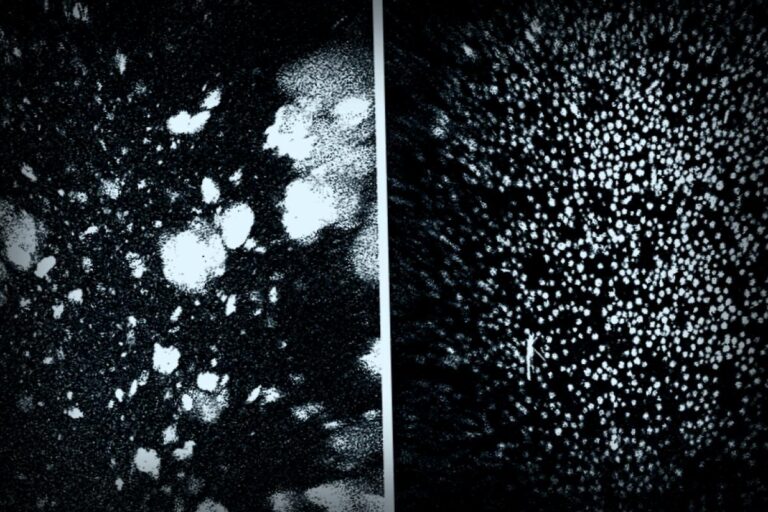

For the recent study, researchers employed a remotely operated underwater vehicle to collect samples from five barrels, scrutinizing different sediment depths including those near the haunting halos. To their surprise, DDT was indeed traced around the barrels but interestingly, amounts remained consistent regardless of sediment depth.

The sediment adjacent to the barrels cloaked with halos revealed heightened pH levels—about 12, nearly equivalent to household bleach—which had resulted in a stark decline in microbial life.

Linking the findings together, researchers theorize that these barrels might be laden with alkaline waste rather than DDT.

Lead researcher Johanna Gutleben, affiliated with the Scripps Institution of Oceanography, expressed, “There has been way more waste dumped in this ocean sector than simply DDT, and so far, we haven’t questioned much beyond DDT itself. Maybe we need to adjust our focus here.”

This caustic waste, as it breaks down around the barrels, has radically changed the local ecosystem. While most basic life forms have disappeared, researchers did identify a few microbial species capable of thriving in these extreme conditions, akin to extremophiles seen in ocean hot vents.

Co-author Paul Jensen, a retired marine microbiologist, shared concerns, mentioning the unsettling effects on not just tiny microbes but the broader aquatic food web.

The fascinating white halos have formed due to the alkaline waste interacting with magnesium in seawater, prompting a mineral called brucite to develop a protective layer in the debris surrounding the barrels. Over time, brucite breaks down and leaves behind halos of calcium carbonate.”,”p>

As the research continues, scientists admit they cannot pinpoint the exact harmful substances generated from these barrels. Yet, they recognize that various manufacturing processes produce alkaline waste, possibly linking these barrels to operations like DDT production.

No one knows the full scale of how much alkaline waste has seeped into the environment. About one-third of the documented barrels exhibit these halos, but it’s unclear if the proportions apply universally to all barrels on the ocean floor, which an earlier assessment warned might exceed 25,000 in count.

In Gutleben’s words, “We simply don’t grasp the scope of the issue yet.”

One thing seems apparent: given that these barrels were discarded over 50 years ago yet continue to contaminate the habitat, the chemicals appearing here are not going away anytime soon. They’ve become new persistent pollutants that resist breaking down easily.

Looking to the future, scientists aim their investigations toward the wider DDT contamination issue in the region. Physically extracting the tainted sediment might not work and could spread DDT further into the water, so their hopes lie on finding microbes capable of dismantling this pollutant.