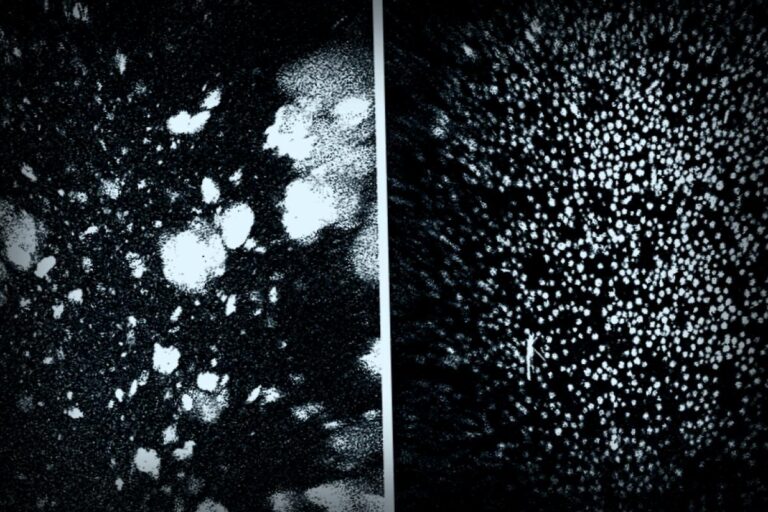

When a team of researchers spotted some strange eroding barrels sitting on the ocean floor off Southern California, they had no idea what they were getting into. The barrels, encircled by an unsettling white halo, are just a tiny fraction of the many that clutter the seafloor in the San Pedro Basin, located between Long Beach and Santa Catalina Island.

This area is notorious for pollution—DDT, a pesticide banned back in 1972, has heavily contaminated the region. Initially, the scientists suspected that these mysterious haloed barrels might contain DDT waste, but the truth turned out to be far more alarming.

Recent research from UC San Diego’s Scripps Institution of Oceanography finally shed light on this mystery. It turns out that these barrels are st with caustic alkaline waste—a seriously corrosive substance that has been leaking into the ocean for decades.

The implications of this pollution are staggering: the toxin creates a harsh environment around the barrels where almost nothing can survive, akin to the extreme habitats near deep-sea hydrothermal vents, yet it’s not a natural presence along California’s coastline.

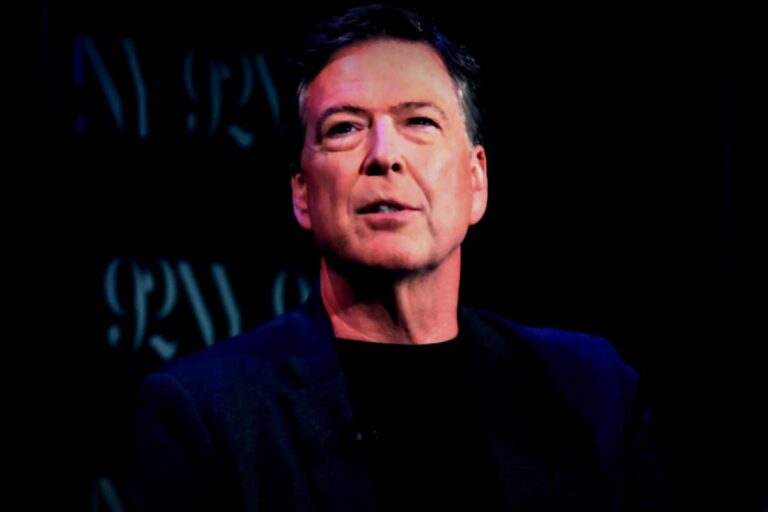

“You wouldn’t expect such extreme conditions out here, and it’s affecting not just microscopic life but all the way up the food chain,” explained Paul Jensen, a retired marine microbiologist from Scripps, who is also a senior author of the study.

This discovery is part of a larger effort among scientists to evaluate sites across the San Pedro Basin. Years of dumping chemicals, including DDT, have escalated environmental risks for both aquatic life and human health.

The research team has unearthed various findings over the years. Interestingly, they found that a significant number of barrel-sized objects on the seafloor were actually leftover munitions from World War II.

Although the researchers aren’t clear on the specific chemicals inside the barrels, they do know that alkaline waste often appeared alongside DDT manufacture and oil refining—both key industries in this region during the mid-20th century.

“We’ve mainly focused on DDT until now, but there’s so much more we haven’t taken into account,” commented Johanna Gutleben, a postdoctoral scholar at Scripps and lead author of the study. “It’s time to broaden our search.”

The presence of DDT has left a long-lasting mark on California’s biodiversity; high levels have been found in endangered California condors and linked to health issues, including cancer in sea lions.

However, what they found seeping from these barrels—located 3,000 feet under the ocean—could be even worse. The study suggests the impacts from the alkaline waste may linger long after the consequences of DDT have diminished.

“What we’ve uncovered is a new type of persistent pollution lurking at the bottom of the ocean, one that’s poised to outlast DDT’s negative effects,” Jensen pointed out. “That really caught us off guard.”

The discovery was partly accidental. Back in 2021, while investigating mineral-rich environments elsewhere, the team decided to detour to the San Pedro Basin to gather samples.

They honed in on five barrels in dumping zones, three of which had those bright white halos. However, sampling didn’t go as smoothly as planned; the seafloor bathed in the hazardous chemical turned hard like concrete, making it tricky to collect samples properly.

Ultimately, they managed to snag a piece of hardened sediment using a robotic arm from a remotely-operated vehicle, taking it to the surface for various tests, including checks for DDT levels and minerals.

The sediment primarily consisted of brucite, which forms when alkaline waste reacts with magnesium in the ocean water, creating a crusty texture that ties everything together around the barrels. High pH levels from the sediment also mixed with seawater to create calcium carbonate, which layers as white dust, adding to those mysterious halos.

Jensen had expected the alkaline waste to disperse quickly into the ocean right after being dumped, but hitting the seafloor and solidifying essentially evolved it into a rock-like form that will likely dissolve slowly over time.

Still, Gutleben emphasizes that many questions remain about the potential widespread effects of this alkaline waste, not to mention the unknown mix of chemicals lurking inside the barrels that brought about their ritualistic dumping into the ocean.

“We don’t even know how many barrels are down there. We can’t tell how many of them could contain this type of alkaline waste, so getting a grip on the entire situation is still a mystery,” she explained.

© 2025 The San Diego Union-Tribune. Visit sandiegouniontribune.com. Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.