Did you know that modern humans and Neanderthals might have interbred way earlier than we previously assumed? Researchers, using CT scans and cool 3D mapping techniques, have been examining the bones of a child that could unlock some exciting insights into our ancient past.

This child, detailed in a recent study from the journal L’Anthropologie, was found in a cave in Israel and dates back about 140,000 years. Although we couldn’t grab any ancient DNA from the remains, scientists believe that hidden details in the bones reveal traits from both ancient human groups.

When archaeologists discovered the child’s bones in Skhul Cave back in 1931, they were puzzled. It didn’t fully match either Homo sapiens, who arrived from Africa, or Neanderthals, who came from Europe. They assumed it belonged to a separate species altogether.

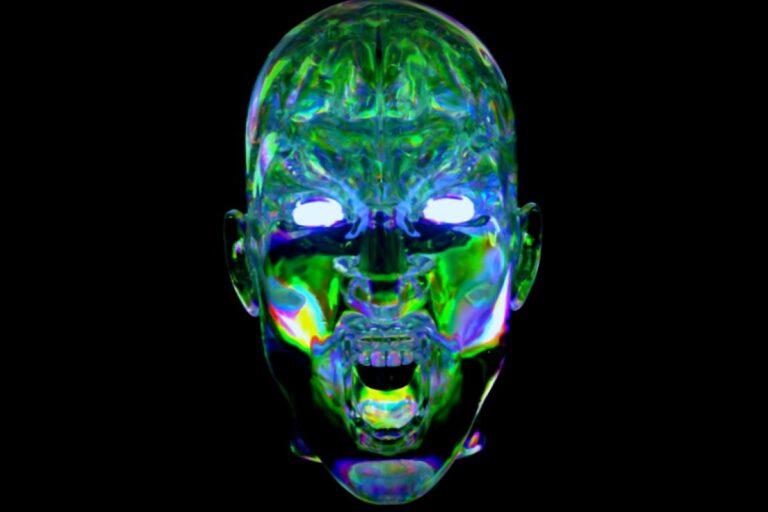

But here’s where it gets interesting! With that nifty 3D mapping, experts could scrutinize intricate details in the child’s skull, like the delicate structure of the inner ear and blood vessel imprints that were previously hard to see.

By comparing specific characteristics of both Homo sapiens and Neanderthals, the team concluded that this child stems from their mingling.

Israel Hershkovitz, who led the study and is a professor at Tel Aviv University, previously thought the earliest interbreeding occurred around 40,000 years ago in central Europe. But this new finding pushes that back a whopping 100,000 years, giving us fresh insights into the bonding between these two groups!

With this research, Hershkovitz points out that there was indeed a meaningful relationship between Homo sapiens and Neanderthals starting around 140,000 years ago, where they seemed to coexist without clashes.

The findings also challenge the stereotype of Homo sapiens as culturally intolerant, as they engaged in shared practices like burial rituals and crafting tools together.

Even though there’s no DNA evidence to concretely prove the child was a hybrid, Pascal Gagneux, an evolutionary biologist at UC San Diego, indicates that the scanning details strengthen that hybrid notion of the child.

The researchers created thousands of scans of the child’s skull and jaw, constructing a detailed 3D model. This tech allows study of tiny features that are impossible to note on fossilized bones, like the blood vessel imprints appearing like “tributaries of a river.” Hershkovitz emphasizes that some of these features illustrate distinct patterns linking back to Neanderthals and Homo sapiens’ differing brain structures.

The reconstructed model provides a glimpse of the child’s skull as much more elongated compared to the original excavated remains—a trait more typical of Neanderthals, according to Gagneux.

However, this reconstruction leaves several questions unanswered. Were the parents of this child also mixed? Or did one belong to the Homo sapiens side and the other to Neanderthals? What’s also curious is why anyone would be buried in that cave?

Thomas Levy, a cyber-archaeology professor at UC San Diego, praised the 3D approach of the study. The advances in visual technology bring a fresh perspective to re-evaluating specimens that have been previously discovered.

About Skhul Cave:

Skhul Cave is notable as one of three famous burial sites dating back over 100,000 years during the Paleolithic era. Various remains have been discovered there, and work on this excavation is ongoing, suggesting this site may offer more answers in the future.

The area of ancient Israel acted as a connector for interactions between Neanderthals and Homo sapiens. Although many think Homo sapiens were aggressive, ultimately leading to Neanderthals’ downfall, Hershkovitz contests this notion, claiming evidence suggests otherwise.

The conclusions drawn from Skhul suggest that humans are not inherently aggressive; rather, behaviors often considered base arose from cultural rather than biological variations. It seems Homo sapiens managed to establish a peaceful coexistence in ways many don’t expect!