Written by Pepper St. Clair

Since life first emerged on Earth, tiny microbes have been at play, altering the habitats that animals must adapt to in their quest for survival. These microbial communities, known as microbiomes, can be found on nearly every surface around us. Recent research has brought to light how octopuses are capable of picking up on signals from these microbiomes, showcasing a unique way through which these intelligent creatures navigate their surroundings.

While humans can detect spoilage in food—like the unpleasant smell of rotten meat or sour milk—we don’t necessarily feel those microbes through touch. Octopuses do things differently. They use their arms to touch and taste the world, an amazing feature considering that their arms are packed with more neurons than the brain itself. Arm muscles are also equipped with specialized receptors that allow octopuses to respond reflexively to specific chemical cues from surrounding microbiomes, according to findings shared in a recent Cell study.

[(https://imgs.mongabay.com/wp-content/uploads/sites/20/2025/11/29164737/Stclairoctopusesandmicrobes1.jpeg)

This is the California two-spot octopus (Octopus bimaculoides). Photo by Anik Grearson.

Microbes aren’t just important for the inner workings of living beings, like influencing development and digestion; they can also impact behaviors exhibited externally. To investigate how microbes might influence animal behavior, a research group led by Rebecka Sepela, who is Postdoctoral Fellow in biology at Harvard University, chose the octopus as their research focus due to its extensive tactile exploration in its environment.

Spencer Nyholm, a microbiologist and invertebrate zoologist from the University of Connecticut, shared insights about the heightened interest in this research, emphasizing the role of microbes as essential elements for both human and animal health.

In a series of experiments, Sepela’s team introduced brooding California two-spot octopuses to assorted microbes that they might encounter on various surfaces in their environment. They crafted fake octopus eggs out of a safe, algae-derived gel and infused them with a specific bacterial molecule derived from real octopus eggs. Remarkably, octopus mothers expelled the artificial eggs that were treated with this molecule much faster than the untreated real eggs.

The team went further, isolating another molecule from decaying crabs to examine the octopuses’ reaction. The animals shunned plastic crab replicas coated with this molecule, responding as if it were a real decaying crab. In contrast, when given regular toy crabs without the signaling molecule, the octopuses held onto them like they would with real prey.

These observations confirm that octopuses can indeed recognize and react to microbial signals. Sepela highlighted this by describing their natural habitat: “They live in a seabed that’s completely covered in microbes.” Given that the majority of an octopus’s body is dedicated to the arms they use for touching and tasting, this capability aligns perfectly with their biology.

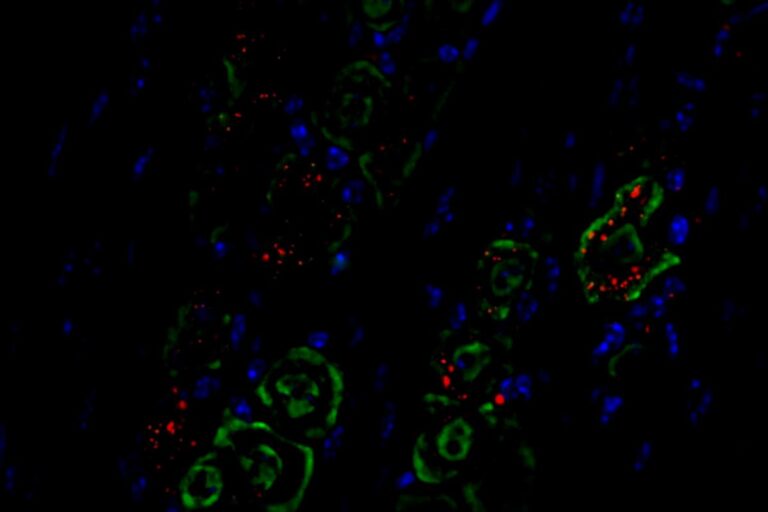

When faced with microbial cues, specific suckers on the octopus’s arms reacted automatically—some would retract or stick to the surfaces with the detected molecules. This reflex is enabled by specialized receptors in the octopus’s suckers that trigger a physiological response once they engage with specific molecules. One receptor, named CRT1, was noted for its versatility in detecting a wide array of molecules.

[(https://imgs.mongabay.com/wp-content/uploads/sites/20/2025/11/29164802/Stclairoctopusesandmicrobes3.jpg)

Here we see Rebecka Sepela and Nicholas Bellono observing behavior in a saltwater tank designed for octopus study. Photo by Niles Singer.

The stunning nature of these findings underscores geometric significance, as articulated by Nyholm. “The world is like a microbial ocean,” he noted, suggesting each creature’s awareness of surrounding microbiomes is pivotal not just for individuals but also for the entire ecosystem.

By unraveling how octopuses perceive their microbial surroundings, we glean insights on how these microbes communicate with particular animal cells. Sepela beautifully summed things up: “It’s fascinating to consider how interconnected we are with an invisible world.”

[(https://imgs.mongabay.com/wp-content/uploads/sites/20/2025/11/29164711/Stclairoctopusesandmicrobes2.jpeg)

A California two-spot octopus (Octopus bimaculoides). Photo by Anik Grearson.

Pepper St. Clairis pursuing a graduate degree in Science Communication at the University of California, Santa Cruz. You can find other articles produced by UCSC students for Mongabay here.

Reference:

Sepela, R. J., Jiang, H., Shin, Y. H., Hautala, T. L., Clardy, J., Hibbs, R. E., & Bellono, N. W. (2025). Environmental microbiomes drive chemotactile sensation in octopus. Cell, 188(18), 4849-4860.e21. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2025.05.033

This piece was first published on Mongabay