Imagine this: more than 200,000 barrels filled with radioactive waste quietly sunk in the North-East Atlantic between the 1940s and 1990s, and all of it forgotten until now. French scientists from CNRS and Ifremer are gearing up to revisit these mysterious underwater graves and see what’s going on down there.

This mission marks the first thorough attempt to locate and study these barrels since dumping them was banned under the London Dumping Convention back in 1990. While these barrels were initially dumped in an area believed to be devoid of life, recent research indicates that these deep ocean floors—over 4,000 meters down—actually host thriving ecosystems. The big question now is whether these ecosystems are in danger due to contamination, and how serious the impact really is.

On May 21, 2025, a press release from the CNRS officially reported the start of NODSSUM, a multidisciplinary adventure pulling together nuclear physics, oceanography, marine biology, and geochemistry. This isn’t just about creating a map of the ocean floor; it’s really about confronting a frightening truth: have we inadvertently poisoned a part of our planet, and if we have, can it be fixed?

The High-Tech Search Begins

Starting from mid-June 2025, the first phase of this significant mission kicked off, with researchers deploying the UlyX autonomous submersible, a cutting-edge robot from the French Oceanographic Fleet. UlyX can reach depths of 6,000 meters and navigate tough underwater landscapes with precision thanks to its high-resolution sonar and real-time imaging capabilities.

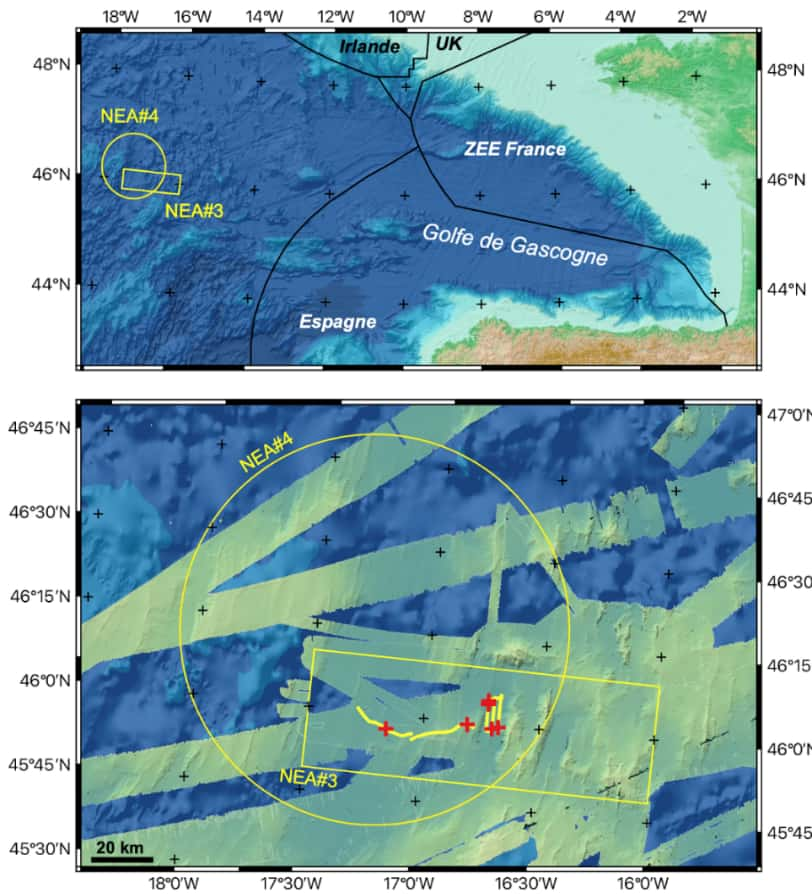

For over a month, the team scoured a massive area of 6,000 square kilometers, targeting the suspected dumping grounds, specifically around NEA#3 and NEA#4, situated in international waters. These sites were initially marked based on Cold War records, yet the exact positions and condition of the barrels remained a mystery.

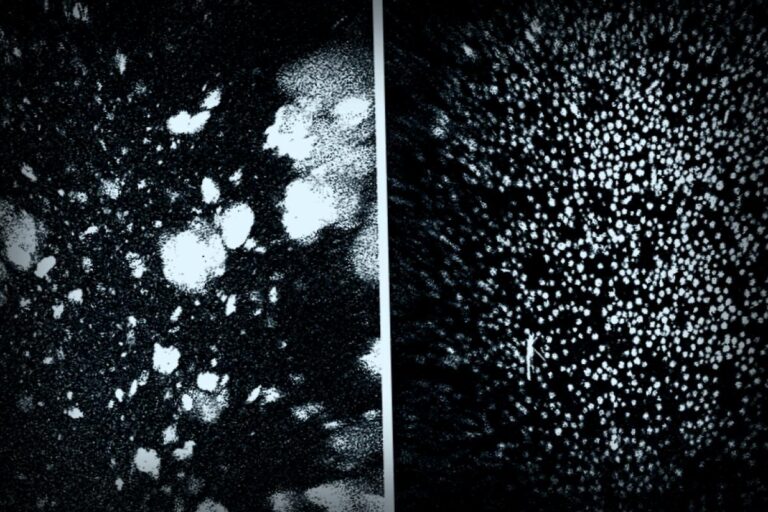

The latest sightings of six barrels date back to 1985, captured in photos by the retired Epaulard submersible during the French’s Epicea initiative. Sadly, no follow-ups ever took place. With stricter environmental regulations and a growing understanding that deep-sea areas aren’t lifeless, this mission clearly comes at a critical time.

Investigating Leaks and Ecological Effects

Once the barrels are found, they will be assessed closely—scanned and photographed. If there are signs of wear or damage, then samples of sediments, seawater, and marine life from surrounding waters will be collected. Researchers are even setting up traps for fish and crustaceans, as well as measuring water currents and collecting sediment cores, to monitor the biological and chemical activities in the vicinity of the waste.

The CNRS scientists assert their aim goes beyond just detecting radiological leaks. They are curious to observe how radionuclides, like cesium-137 or plutonium-239, might be impacting the local ecosystem. These radioactive materials can hang around for years, if not centuries, sticking to particles, collecting in marine creatures, and gradually making their way up the food chain.

Everything the scientists learn will feed into a broader scheme called PRIME RADIOCEAN, a French government-supported initiative designed to develop effective methods for long-term monitoring of radioactive pollutants in our oceans.