In an exciting development, researchers monitoring whale breathing patterns from drones have identified a potentially harmful virus circulating in the Arctic Circle.

The analysis of whale ‘blows’ confirmed the existence of cetacean morbillivirus, a pathogen that affects various marine mammals such as whales, dolphins, and porpoises.

This virus is known for its high transmission rates among species and the ability to create large-scale mortality events across oceans.

Many stranding events of these magnificent creatures are believed to be linked to this infectious disease.

During the study, several whale species, including humpbacks, sperm whales, and fin whales, were examined in the northeastern Atlantic region.

One notably affected specimen was a pilot whale that ended up on the shores of northern Norway.

Furthermore, herpesviruses were also detected in some humpback whales off the coasts of Norway, Iceland, and Cape Verde.

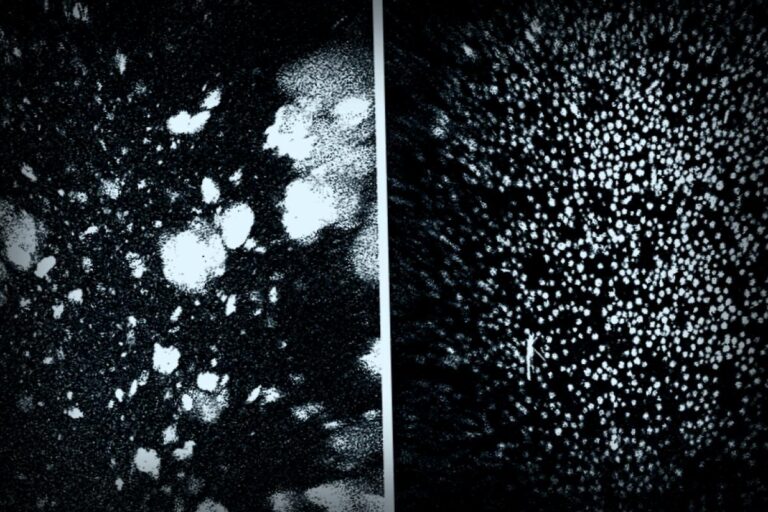

The innovative drones employed capture water droplets using petri dishes, allowing scientists to analyze these samples for any harmful pathogens.

Alongside this, the team collected skin biopsies and one organ sample to test for various infections.

These samples were gathered as the whales surfaced for air, exhaling through their blowholes.

This important research involved collaboration between King’s College London, The Royal (Dick) School of Veterinary Studies, and Nord University in Norway.

Professor Terry Dawson from KCL stated that this study would significantly enhance our understanding of marine health without causing harm to the whales.

Helena Costa from Nord University mentioned that these methods could serve as valuable ‘long-term surveillance’ tools to gather data on how these viruses impact whale health over time.

Alarmingly, up to 2,000 cetaceans wash ashore annually, a trend that this research aims to combat.

The cetacean morbillivirus was first identified in 1987 and is known to cause severe damage to respiratory, neurological, and immune systems in affected species.

The latest findings spark concern over potential virus outbreaks during the critical winter feeding period, a time when whales, seabirds, and humans often come into close quarters.