Let’s break down what this exciting study reveals:

- The mission focused on the mantle, the Earth’s biggest layer, by drilling deep cores from our planet.

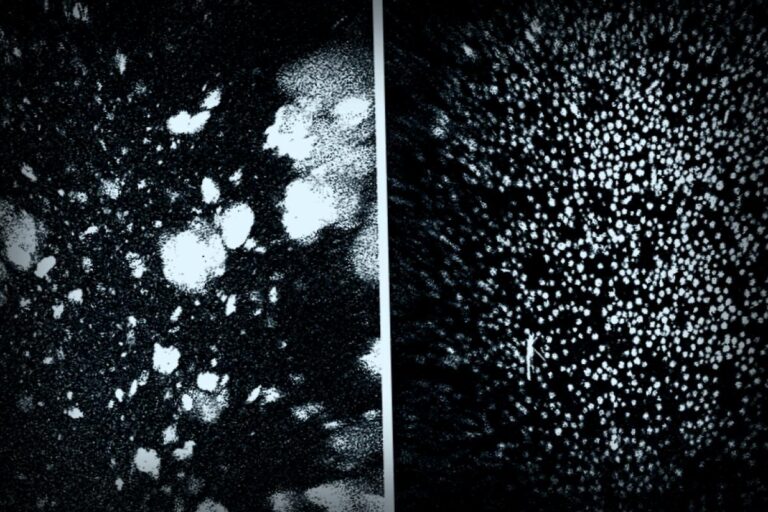

- For the first time, scientists managed to retrieve serpentinized peridotite, formed when seawater interacts with mantle rock.

- While this is the closest anyone has reached to the mantle, the expedition did not fully penetrate the pristine mantle beyond the Moho boundary.

If geology fascinates you, the mantle is a vital topic. It separates the rocky crust and the molten outer core, comprising about 70% of the Earth’s mass and 84% of its volume. Yet, until now, scientists had never managed to directly sample rocks from this crucial layer.

Drilling is tough due to the crust’s significant thickness, around 9 to 12 miles. Fortunately, some locations on Earth have unusually thin crust that reveals mantle structures. One highlight is the Mid-Atlantic Ridge, especially around an underwater peak called the Atlantis Massif.

On the southern flank of this massif lies an area termed the Lost City, known for its hydrothermal vents. The vent fluids there are not just any seawater; they are rich in hydrogen, methane, and a range of carbon compounds, making it an intriguing site for uncovering the origins of early life on Earth. The rocks in this region undergo a transformation called “serpentinization,” resulting in a green, marble-like surface.

In May 2023, located 800 meters south of the Lost City, researchers from the International Ocean Discovery Program (IODP) boarded the JOIDES Resolution—a 470-foot-long research vessel funded by the U.S. National Science Foundation. They managed to pull a core sample that measured 1,268 meters, containing abyssal peridotites, the primary mantle rocks of Earth. The study’s findings are detailed in a report in the Science journal.

The deeper core they collected marks a new record, yet achieving this depth wasn’t part of the initial plan for the expedition.

“Our initial goal was to drill about 200 meters because that’s been the former depth record for mantle rock,” said Johan Lissenberg, a co-author of the study and a petrologist at Cardiff University. He noted they progressed much faster than expected, allowing the team to maintain a pace three times quicker than normal. Ultimately, they drilled a staggering 1,268 meters, stopping only due to the finite duration of the mission.

Another study co-author, Andrew McCaig from the University of Leeds, explained in an article from The Conversation that initial analyses show the core comprises a type of peridotite called harzburgite formed by partial melting of mantle rock. It also consisted of gabbros, coarse-grained igneous rocks that reacted chemically with seawater, altering their makeup.

This successful core sampling presents an invaluable chance to deepen our understanding of the mantle and the geologic base that supports the Lost City. However, the mission still fell short of fully crossing the Moho— the boundary separating the crust from the immaculate mantle.

Future explorations might probe further into Atlantis Massif, but sadly, the JOIDES Resolution won’t take part, as the National Science Foundation is not funding any more core drilling after 2024. Just when scientists are on the tip of exploring this fundamental geological layer, the movement for these drilling tasks has suddenly become uncertain.

[galleryCarousel id=’9e9354e9-d0c6-426e-ba21-7d41e95744de’ mediaId=’07dd9425-4530-44b7-a993-e19d39be1557′ display=’carousel’ align=’center’ size=’medium’ share=’true’ expand=” captions=’true’ suppress-title=’false’ hasProducts=’false’][/galleryCarousel]