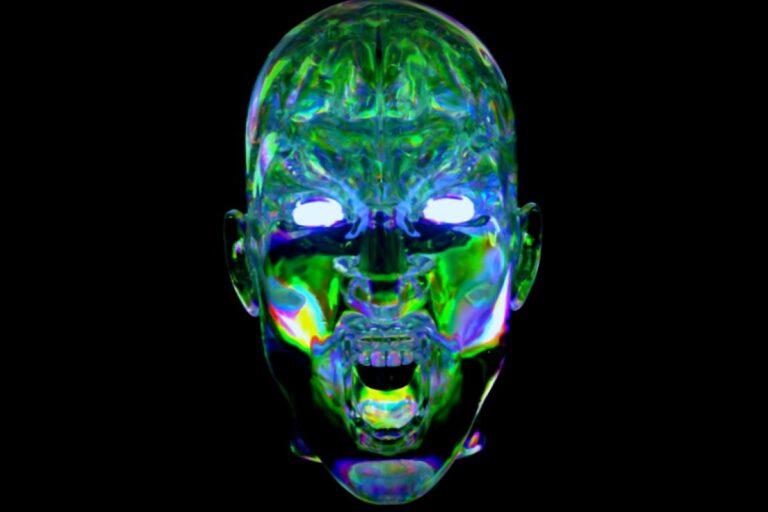

For almost a century, a curious strip of around 5,200 holes, extending nearly one mile (1.5 kilometers) in the Pisco Valley of southern Peru, has left experts scratching their heads. However, recent studies of the Monte Sierpe site — playfully d “serpent mountain” — are shedding light on why ancient peoples carved these features into the landscape.

The fascination with the “band of holes” kicked off back in 1933 when National Geographic showcased aerial views of the area.

Despite their potential significance, there’s a lack of written records concerning the purpose of these holes, making it a subject of wild speculation over the years. Suggestions about their function have ranged from serving as defenses to assisting with agriculture and even being part of alien visits, according to proponents of the ancient astronaut theory.

Now, armed with new drone visuals and detailed analysis of pollen found within these intriguing holes, researchers propose that this location first operated as a bustling marketplace for pre-Incan societies, eventually transforming into an accounting tool for the Incas. This new insight was shared in a study published on November 10 in the journal Antiquity.

“It’s astonishing to ponder — why would ancient communities create over 5,000 holes in the Andes?” Dr. Jacob Bongers, the leading researcher from the University of Sydney, remarked. “While we still don’t know exactly what they were for, recent findings point us in a promising direction that offers vital insights and supports fresh interpretations of the site’s function.”

Diving Deeper into History

The impressive scale of Monte Sierpe has made it a tough nut to crack for archaeologists, but the use of drone tech has opened new avenues for exploration, according to Charles Stanish, a co-author of the study and anthropology professor at the University of South Florida.

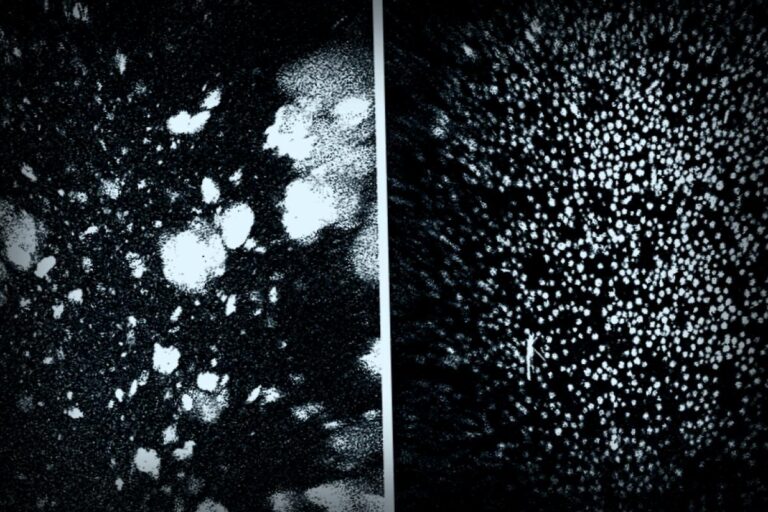

Each hole varies from about 3.3 to 6.6 feet (1 to 2 meters) wide, and 1.6 to 3.3 feet (0.5 to 1 meter) deep. Drone imagery shows these holes divided into roughly 60 clusters, with noticeable spaces in between, highlighting a level of organization rather than randomness. Bongers noted patterns within the structure, such as 12 alternating rows of holes, hinting at intent behind their arrangement.

Pollen grains uncovered from inside the holes lead to the discovery of ancient crops — like maize — as well as local flora that traditional basket weavers would recognize. This raises the potential that goods or crops were stored in these types of baskets, possibly lined with plant materials resting in the holes.

It’s plausible that additional structures once stood near these holes, yet no architectural evidence has surfaced thus far.

The theory posits that the ancestors from what used to be the Chincha Kingdom traded and exchanged items using this site without the context of a monetary system.

“Essential goods like cotton, coca, maize, and chili peppers may have been placed in the holes, suggesting a barter economy,” Bongers proposed. “One type of good, like maize, would have been traded for another, like coca, through an agreed number of holes.”

The pollen findings effectively negate many other theories about how the site was used. Dr. Dennis Ogburn, an associate professor at UNC, pointed out that Monte Sierpe has puzzled archaeologists in the Andes for far too long, making the ongoing research all the more thrilling.

Understanding the Landscape

Investigations into dating reveal that the site thrived roughly 600 to 700 years ago. While the research team continues fine-tuning the timeline through radiocarbon dating, they believe the features primarily date back to Peru’s Late Intermediate Period, between AD 1000 and 1400.

Pollen from citrus plants indicated post-colonial-era activity indicating that the holes were in use even after the fall of the Incan Empire in 1532, as Spanish influence gathered pace in Peru’s structure. Bongers suspects the site fell out of use because it didn’t mesh with the Spaniards’ economic ambitions.

Monte Sierpe may have started as just a few holes for bartering but likely expanded to cater to the Inca’s needs.

Bongers likened it to an ancient “Excel spreadsheet” that the Incas might have utilized for broader accounting tasks.

Interestingly, the layout of the site reflects a unique counting method employed by the Incas, called a khipu, where cords knotted to denote numbers were crucial for record-keeping. One such khipu was found in the nearby Pisco Valley, suggesting a soothing parallel for these holes linking back to ancient Colorado.

Situated perfect for commerce and record-keeping, Monte Sierpe was wedged between prominent Incan sites — Tambo Colorado and Lima La Vieja.

In light of Bongers’ ongoing efforts, there’s a keen aim to analyze existing khipus in Peru for any numeric relationship to this unique design. If connections are confirmed, it might have played a pivotal role in local tribute collection — an early taxation concept.

Despite differences between commerce methods and potential ties to Inca khipus theory, scholars like Ogburn suggest more proof is crucial before embracing concepts conclusively.

Guarding Our Ancestral Legacy

As fresh research endeavors dig deeper into the enigma of Monte Sierpe, upcoming discoveries could illuminate a historical aspect dimmed over time.

“The Andes hold one of the few globally significant large-scale societies like the Inca Empire, but evidence of pre-Hispanic currencies or writing is sorely lacking,” Bongers remarked.

Dr. Christian Mader from the University of Bonn underscores the significance of this research, noting it’s a valuable step forward in the study of Peru’s ancient economies amid his expertise in pre-Hispanic exchanges. Mader commended them for the idea that Monte Sierpe served dual roles as a trading site and a record-keeping structure under Incan rule, showing we still really have much to uncover about indigenous economies.

Bongers concluded that Monte Sierpe represents a multilayered narrative requiring careful examination of ideas that can be challenged and explored to honor local folklore more accurately.

“Stories we weave about local heritage matter,”) ಪುಸ್ತಕ आखिर में, ) said Bongers;· “)We must guarantee these stories genuinely reflect indigenous views and underscore archaeological evidence to portray local cultures authentically.