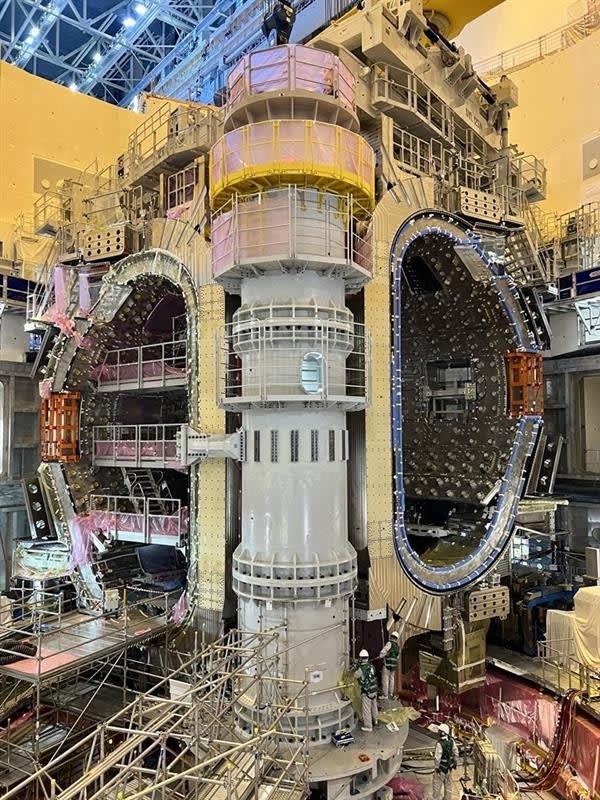

In beautiful Provence, France, something incredible is happening. The ITER project, considered one of the most ambitious scientific ventures ever, is hitting a significant turning point. Here, engineers are busy building a reactor meant to recreate the same nuclear fusion reactions that fuel the sun and stars.

Once completed, this reactor will face the awe-inspiring task of controlling superheated plasma at eye-watering temperatures that exceed 150 million degrees Celsius. It’s not just an engineering feat; it’s a game-changing bid for the future of clean energy, with the potential to transform how we power our world.

Development of the ITER fusion reactor has spanned nearly two decades, and the focus is now shifting gears from design to assembly—a stage that involves an unmatched level of complexity and scale in the energy sector.

Nuclear fusion is often touted as the holy grail of energy. Why? Because it promises access to essentially limitless, carbon-free energy without the long-lasting radioactive waste or meltdown risks of traditional nuclear fission. ITER’s mission is to demonstrate that fusion can be realized on a scale suitable for powering entire cities.

Building the Tokamak: Precision Engineering Under Tough Conditions

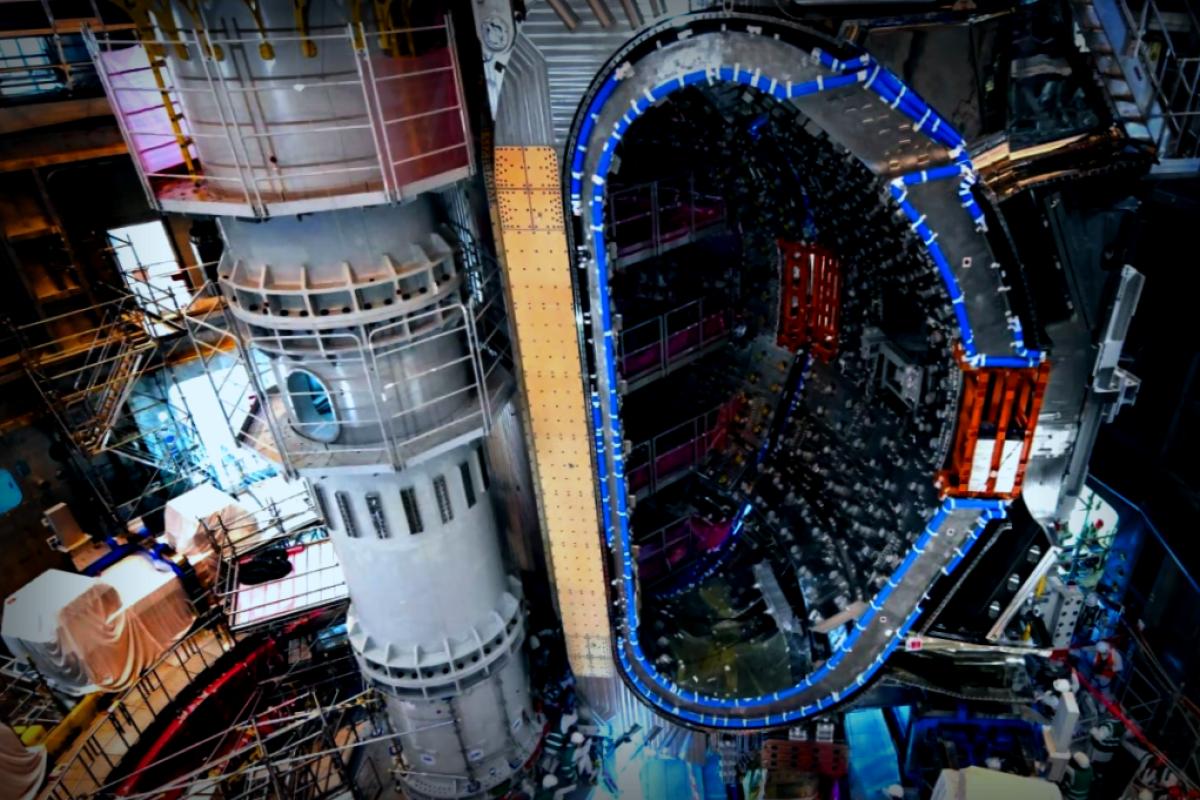

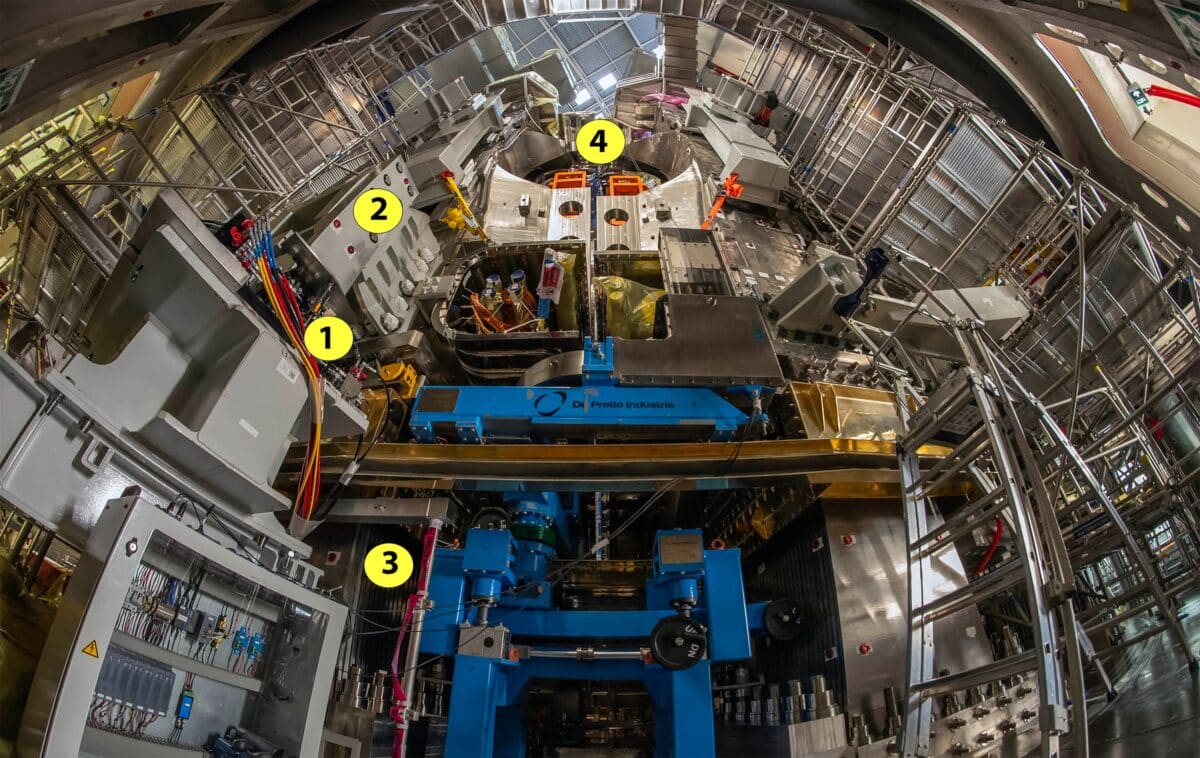

The heart of ITER is its remarkable vacuum vessel, a massive 19-meter-wide stainless steel chamber designed to contain plasma where hydrogen nuclei will fuse together into helium, thereby unleashing enormous energy yields. The construction consists of nine heavy steel sectors, each weighing around 440 tonnes, shipped from both Europe and South Korea.

Once fully assembled and sealed, the structure will tip the scales at over 5,200 tonnes and must be aligned with extraordinary precision—within mere millimeters. The American company Westinghouse is steering the assembly, alongside European partners like Ansaldo Nucleare and Walter Tosto.

But it’s not just a walk in the park. If the plasma touches the walls, the fusion reaction could shut down. Achieving precise alignment, welding, and controlling distortions—all while managing extreme heat and pressure—calls for unprecedented engineering accuracy.

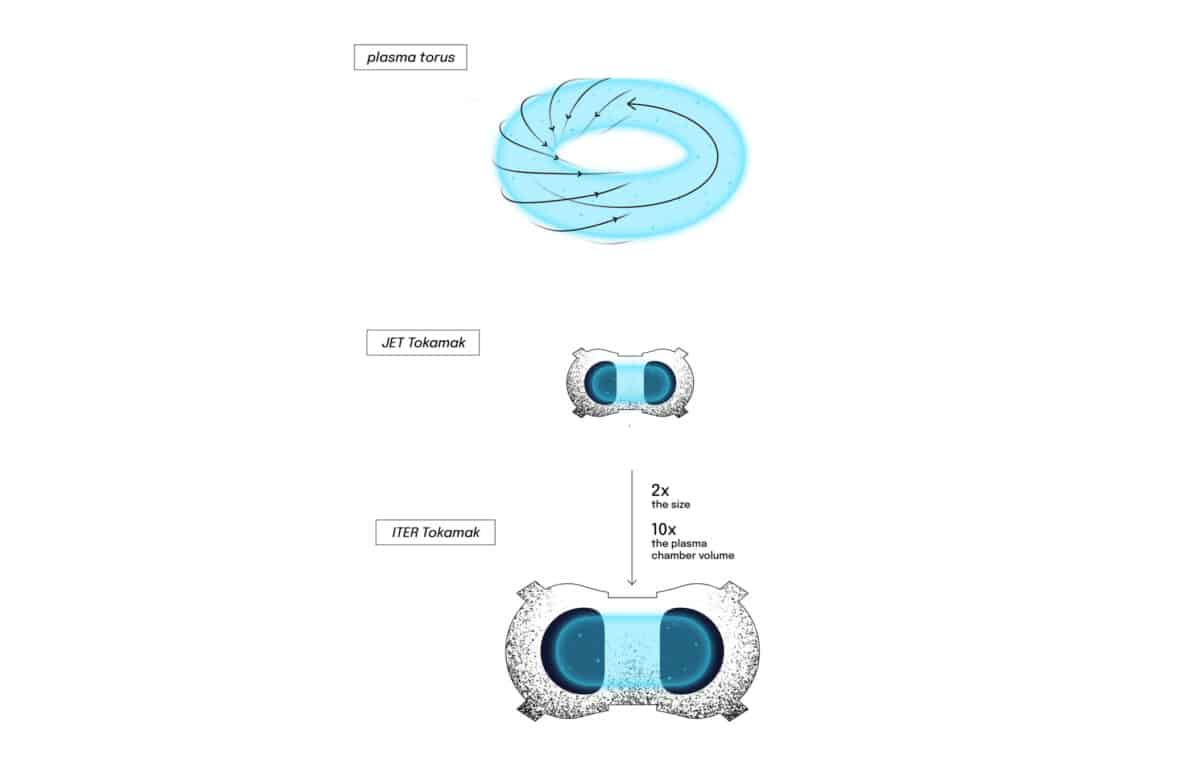

Inspired by Soviet designs, the tokamak remains a leading strategy for controlled thermonuclear fusion. ITER’s setup will be the largest ever crafted, boasting a plasma volume of 830 cubic meters, which is eight times larger than existing fusion vessels.

An International Collaborative Effort

Even though it’s located in France, ITER isn’t just a French initiative. It’s a powerful example of scientific collaboration involving 35 nations, including the USA, China, Russia, Japan, India, South Korea, and all European Union countries.

Nations are pitching in with various parts of the reactor. The European Union covers five of the nine vessel sectors, while South Korea supplies four. The United States has contributed massive superconducting magnets over 18 meters long, and Japan provides crucial components for the central solenoid, the heavy-duty electromagnet that drives the plasma current.

Believe it or not, over 100,000 kilometers of superconducting wire—enough to circle the globe twice—has been created for ITER’s magnet system. This required enormous growth in global manufacturing capabilities to ensure these parts could be transported via the unique ITER Itinerary, a specially modified 104-kilometer route designed for items weighing up to 900 tonnes.

This sort of multinational cooperation is a rarity in energy research, requiring meticulous synchronization across several time zones and corners of the planet. The entire process is often d a massive scientific and logistical jigsaw puzzle.

Paving the Future of Fusion Energy

Fusion energy tantalizes us with significant pros over other clean energy methods. It leverages hydrogen isotopes, widely obtainable from seawater and lithium, as its fuel source. There are no carbon emissions, and it generates No long-lived radioactive waste, nor does it risk a meltdown. Plus, fusion’s energy density far surpasses fossil fuels by millions of times, and it doesn’t rely on weather or sunlight.

ITER aims to deliver 500 megawatts of fusion power using only 50 megawatts of input energy; that’s an extraordinary tenfold energy return known as Q = 10. If this goal is met, it will surpass the existing records set by the JET facility in the UK, which reached a measly Q = 0.67.

Yet, it’s important to note that ITER won’t be powering homes directly. Its successor, DEMO, a future commercial fusion power plant currently in the design phase in Europe and Asia, will take on that responsibility.

As with many projects of this magnitude, timelines have fluctuated. Initial hopes for a first plasma in 2018 have since adjusted. New targets are now set for:

- Deuterium-deuterium operations beginning in 2035

- Complete plasma current and magnetic field testing slated for 2036

- Switching to deuterium-tritium fusion experiments by 2039

The latest timeline was confirmed in ITER’s July 2024 Baseline Update, detailing the path ahead towards full fusion operations. After ignition, the next challenge is ensuring it can be sustained for long durations and ramped up to commercial reactors to power cities consistently.