In July, experts from Cedars-Sinai connected with fellow scientists from around the world at the Alzheimer’s Association International Conference. This event showcased various scientific advancements, including data from clinical trials focusing on potential therapies for Alzheimer’s disease.

According to Dr. Mitzi Gonzales, director of Translational Research at the Jona Goldrich Center for Alzheimer’s and Memory Disorders, over 90% of Alzheimer’s clinical trials fall short of their intended outcomes. However, she emphasized that there’s always valuable knowledge to be gained from each trial.

Dr. Gonzales remarked, “Even the trials that don’t hit the mark are super important in redefining our understanding of the disease. When we discover that a particular pathway isn’t effective, it can lead us to explore new approaches.”

For example, the recent findings from a trial led by Dr. Gonzales involved a drug known as rapamycin. Prior research suggested that rapamycin might promote longer life and alleviate several age-related ailments.

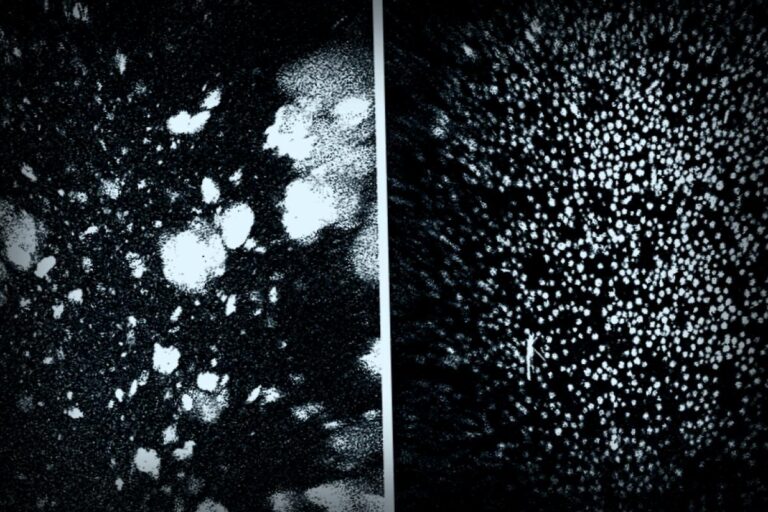

This study has been documented in the journal Communications Medicine. Dr. Gonzales explained, “Initial studies indicated that rapamycin helped reduce harmful accumulations of amyloid beta and tau proteins in the brain, known contributors to Alzheimer’s. We hoped to replicate these effects in human subjects.” Unfortunately, the results showed an increase in amyloid and tau levels instead.

According to Dr. Gonzales, “This outcome raises new scientific questions and opens up additional research paths. It has directed us to investigate whether the drug might work better in earlier stages of the disease.”

Dr. Sarah Kremen, director of the Neurobehavior Program, highlighted that even samples collected during trials that don’t yield successful treatments can still illuminate future breakthroughs.

Referring to the significant A4 study which tested the drug solanezumab among cognitively healthy individuals with elevated amyloid levels, Dr. Kremen mentioned, “Although the drug failed to enhance cognition or decrease amyloid, it marked a crucial moment since it was the first time we studied asymptomatic but at-risk individuals. It was a major step forward!”

This research contributed to discovering the pTau217 biomarker, an early indicator of Alzheimer’s, which is now a key element in the FDA-approved blood test for identifying amyloid plaque accumulation in the brain, as explained by Dr. Kremen.

Ultimately, both Dr. Gonzales and Dr. Kremen point to the multifaceted challenges of Alzheimer’s, such as its diverse causes and the long timeframe before symptoms become apparent, along with the intricate nature of the brain.

Dr. Kremen concluded, “Our understanding of the brain is not as advanced as it is for some other organs, and the processes behind neurodegenerative diseases are complex. It’s going to take time—along with many more clinical trials—to decipher the various mechanisms that contribute to Alzheimer’s disease.”

For more information: Mitzi M. Gonzales et al, “Rapamycin treatment for Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias: a pilot phase 1 clinical trial”, Communications Medicine (2025). DOI: 10.1038/s43856-025-00904-9

Provided by Cedars-Sinai Medical Center