In a bold move showcasing Moscow’s resolve to keep its Arctic routes open for business, Russia has simultaneously dispatched its full fleet of eight nuclear-powered icebreakers for the very first time. Given recent discussions regarding the shortcomings of the Russian Navy’s Black Sea Fleet, it’s tempting to generalize this lack of naval prowess to all aspects of Russia’s maritime operations. Yet, this oversimplification overlooks the significant achievement of operating these complex ships under harsh Arctic conditions all at once.

With winter fast approaching and ice cover increasing in the Gulf of Ob and Yenisei Gulf, these icebreakers are essential for clearing paths for tankers transporting oil, liquefied natural gas, and various minerals from remote northern terminals. This month’s thick ice brings a reminder of just how essential these sea routes are for Russia’s “Extreme North,” and the lengths to which President Putin is willing to go to safeguard them. One thing is clear: he needs continuous access to Vital oil and gas supplies to keep his war economy running.

Russia boasts the only operational fleet of nuclear icebreakers in the world, including four advanced Project 22220 models (Arktika, Sibir, Ural, and Yakutiya), two older Arktika-class vessels (Yamal and 50 Let Pobedy), and two shallower Taymyr-class ships, supported by about 40 traditional icebreakers. What puts Russia ahead is that these nuclear icebreakers have capabilities that are unmatched by any Western power. Unlike typical vessels, which face limits on how much power they can sustainably apply, having greater thrust in icebreakers allows them to punch through denser ice, and with nuclear power, they can sustain high performance without fuel constraints.

These unique features mean that Russian icebreakers can operate all year round in the challenging Arctic. This allows for uninterrupted oil and gas flows from the Gulf of Ob even throughout winter, helping keep the Northern Sea Route navigable for more extended periods, which reduces transit times to Asia and circumvents bottlenecks like the Suez Canal. Although ordinary shipping or ice-class vessels often can’t navigate through thick ice, the presence of these icebreakers dramatically boosts their chances of successful passage.

For Putin, maintaining operations in the Arctic is critical for economic stability. The foothold of Arctic projects on Russia’s GDP is already substantial, especially as the country redirects oil and LNG exports eastward in the face of Western sanctions. Last year, they managed to move nearly 38 million tonnes of cargo, with expectations for a 20% increase by 2025 due to Yamal LNG and additional terminals.

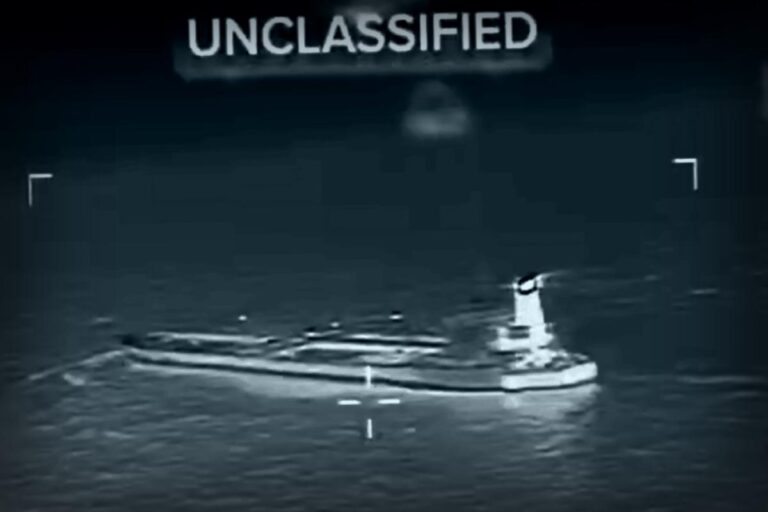

In contrast, sanctions imposed globally have triggered the emergence of a “dark fleet” composed of aging and often unreliable tankers dodging Russian oil price caps. Unfortunately, some are increasingly attempting to navigate the Arctic routes to reach China. One LNG carrier recently attempted to transit the Kara Sea, but failed and had to retreat. This situation raises alarms about potential ecological disasters—it’s just a matter of when and how severe it will be, with incidents around Venezuela, including the US seizure of the tanker Skipper, only amplifying the risk.

When it comes to nuclear-powered icebreakers, Russia is truly in a league of its own. While Finland, Canada, and Sweden maintain conventional icebreaker fleets, China is developing its own fleet but lacks nuclear capabilities at this stage. Notably, America’s presence in the Arctic is surprisingly underwhelming; the US Coast Guard operates merely two aging heavy icebreakers, despite the Arctic’s strategic importance to the nation. While former President Trump attempted to ramp up initiatives by signing a memorandum with Finland to produce up to 11 new Arctic Security Cutters, progress on delivering these has been slow.

The UK is not much better off with just two icebreakers: the Royal Navy’s HMS Protector and the research-oriented RRS Sir David Attenborough. There have been speculations of another Royal Naval icebreaker being considered, with logic that one could service the South Atlantic and another for the High North—a second ice-class vessel would significantly extend operational capabilities in the region, especially as part of the new Atlantic Bastion strategy aimed at countering Russian submarine activity in the Barents Sea, facilitating research in crucial water columns. Extending search zones up to the ice line would also contribute to boosted efficiency.

Like many defense developments at present, we’ll have to bide our time for the upcoming Defense Investment Plan set to debut early next year, waiting to see whether these rumors evolve into reality or fade away.

Shifting back to Siberia, the operation of all eight nuclear icebreakers functioning simultaneously is indeed a remarkable feat. However, this effort isn’t without ramifications—it’s neither sustainable nor without costs in financial or operational terms down the line, serving as a tense barometer of the immense pressure President Putin and the Russian economy currently face.

Tom Sharpe OBE served in the Royal Navy for 27 years, commanding various warships including the icebreaker HMS Endurance.